By Brian Santo, contributing writer

Most places associated with the early development of electricity and electronics are gone, but there are still sites where engineering history persists and can be visited. Summer’s coming, and it’s time for a good, old-fashioned family road trip. Pack up the station wagon, hit the road, and take in the sights.

A potential bonus of a technology-based road trip? The odds of bumping into vacationers like the Griswolds are going to be vanishingly small at these places.

William Faulkner wrote, “The past is never dead. It’s not even past.” If that’s even true, it’s still significantly less true about historical landmarks. Landmarks seem to be easily forgotten, especially if the site has something to do with science and engineering.

Perhaps that’s understandable. Scientists and engineers tend to be both practical and unsentimental. If you can’t use it, what good is it? Obsolescence can come quick, whether it’s a facility or a product. Buildings get razed, labs get demolished, and devices — tools, towers, test beds, prototypes — get dismantled, recycled, or trashed.

The work that goes on in laboratories can be every bit as momentous as what happens on battlefields, but the sites of scientific achievements are not always as actively commemorated. There is no question that Edison’s remarkably well-preserved lab in West Orange, New Jersey, for example, is at least as worthy of a visit as the fields at Gettysburg, but anything associated with Edison is more the exception than the rule.

Recognition is not completely lacking, however. Multiple professional organizations have set up programs to recognize sites that are important to science history. The IEEE, for example, has its Milestones Program to point out such sites.

Some of these places on our list here have been preserved, some commemorated with plaques, others are noted only with addresses on devotional webpages, some not even that. Some are well-known and frequently visited, while others are off the beaten path.

Historic Speedwell

Address: 333 Speedwell Ave., Morristown, NJ

Website: https://www.morristourism.org/directory/historic-speedwell/

Samuel F.B. Morse did not invent the telegraph (Ampere and others preceded him), but he did come up with the first version that was practical for commercial purposes. First, though, his version had to be built, tested, and proven. One of Morse’s former students, Alfred Vail, volunteered for the task.

In 1838, on the Vail family farm, Morse and Vail collaborated on the first successful public demonstration of their system. Electric pulses traversed two miles of wire. At the receiving end, a device based on an electromagnet inked dots and dashes on a strip of paper.

The first message was for Vail’s father, who, two years prior, had put up the money for the development, and who had grown skeptical that he’d see any return on his investment. It said, “A patient waiter is no loser.”

“The Birthplace of the Telegraph” is now an interactive telecommunications museum. Speedwell is a National Historic Landmark and an IEEE Milestone .

The Speedwell Ironworks factory building, where Morse and Vail demonstrated the first practical telegraph system. (Source: Wikimedia Commons. Photographer: Leif Knutsen.)

Thomas Edison National Historical Park

Address: 211 Main St., West Orange, NJ

Website: https://www.nps.gov/edis/index.htm

The Wizard of Menlo Park set up his last and largest laboratory not too far from his home, Glenmont, which is also part of the historical park and open for tours. The West Orange facility is the modern model for R&D labs.

There are 14 structures, built for a variety of pursuits, with separate buildings for experiments in chemistry, physics, and metallurgy. The site houses over 400,000 artifacts, including prototypes and commercial Edison products, laboratory furnishings and equipment, and personal items used by the Edison family. The on-site archive includes an estimated 5 million documents, 48,000 sound recordings, 10,000 rare books, 4,000 laboratory notebooks, and 60,000 photographic images.

The site is both a National Historical Park and IEEE Milestone .

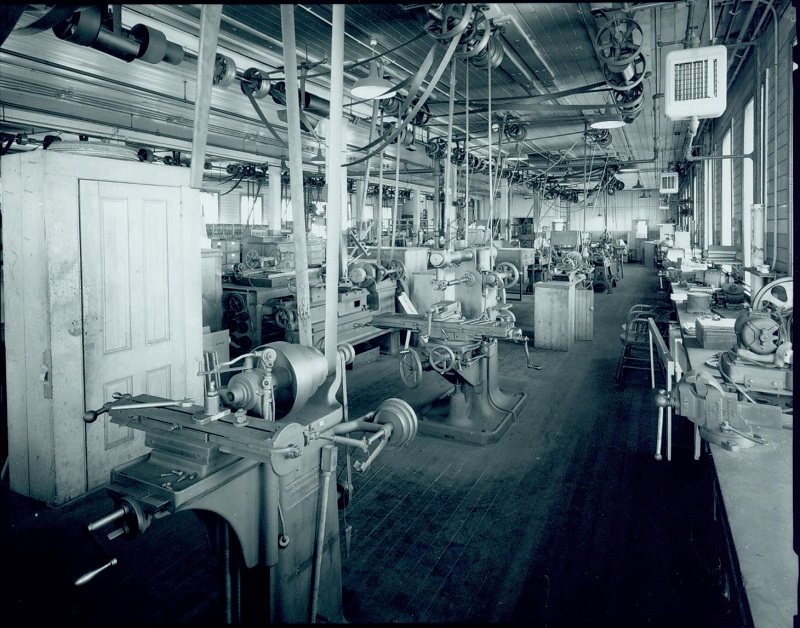

Edison’s West Orange precision shop before renovation. (Source: U.S. National Park Service.)

The Hewlett-Packard garage

Address: 367 Addison Ave., Palo Alto, CA

No official web site, but there is an HP brochure .

In the early 1900s, Palo Alto, California, was mostly farmland, but engineering professors at Stanford University encouraged enterprising students to set up shop nearby rather than taking jobs elsewhere.

When Dave Packard and Bill Hewlett decided to form a company, they were among the first — if not the first — to act on that advice. Packard and his wife rented the ground floor of the house (the landlady lived upstairs); Hewlett lodged in a backyard shed. The two men converted the garage into a workshop, and that’s where they designed and built some of HP’s first products, including the Model 200A audio oscillator.

The two men became the first notably successful electronics entrepreneurs in the area. Gradually, more and more companies set up shop in the vicinity — so many that, years later, the area was dubbed Silicon Valley by trade paper Electronic News.

The Packards’ garage was long considered the birthplace of Silicon Valley, and in 1989, California officially designated it as such. HP bought it a few years later. There are no tours, but the garage is marked by a plaque in the front yard and can be seen from the street. It is a California Historical Landmark and is listed on the National Register of Historic Places.

![]()

The HP garage, birthplace of Silicon Valley. (Source: Wikimedia Commons.)

Adams hydroelectric transformer station

Address: 1501 Buffalo Ave., Niagara Falls, NY

Unofficial website: http://www.edisontechcenter.org/Niagara.htm

The Adams transformer station is the last structure still standing from what was, in 1896, the largest AC power plant in the world. That is its only distinction as a power plant — it wasn’t even the first hydroplant at Niagara Falls. And yet, the Adams hydroelectric facility is unquestionably among the most famous power stations in the world due to its location and the personalities involved.

Those who know one thing about the Adams hydroelectric plant know that it was the project that demonstrated, finally, the superiority of AC. From a technological standpoint, the competition between Thomas Edison, with his DC system, and George Westinghouse, who championed Nikola Tesla’s AC power system, was already pretty much over by then. Publicly, however, the Westinghouse-Edison competition was still headline material.

Ultimately, both Westinghouse and Edison’s GE would get contracts for the plant. Both men understood the value of publicity, and both touted the project, which lent itself to hyperbole. It was a big project; it was located at one of the most majestic natural sights in the world; it involved boring a massive tailrace tunnel; and the transformer house was designed by noted architect Stanford White. The plant was gradually expanded to supply 37 megawatts for the growing city of Buffalo, New York.

Today, the transformer house is fenced off, but can still be viewed from the road. It is on the National Register of Historic Places. It was designated a National Historic Landmark in 1983 and is an IEEE Milestone .

Adams hydroelectric plant. (Source: Wikimedia Commons.)

Signal Hill

230 Signal Hill Road, St. John’s, NL

Website: https://www.pc.gc.ca/en/lhn-nhs/nl/signalhill

Guglielmo Marconi received the first transatlantic signal on this site in 1901. He set up shop in an abandoned hospital ward on the flank of the hill, just below Cabot Tower . That former hospital building is now gone, but the event is commemorated at a visitor center.

Cabot Tower remains, however. It had been completed just the year before, and there are pictures of Marconi standing in front of it. The Tower has another solid connection with the wireless pioneer, though. Three decades after Marconi received that first transatlantic wireless transmission — a Morse code “S” — Cabot Tower would become one of the Marconi Wireless Corp.’s telegraph offices.

Marconi had planned to receive the first transatlantic wireless signal in Boston, but the original tower at the other end, in Poldhu, Cornwall, England (itself an IEEE Milestone), collapsed. The replacement was shorter, and Marconi feared that the signal might not make it all the way. Newfoundland is closer to Cornwall by far than Massachusetts.

Signal Hill also happens to be the site of the last major North American battle in the Seven Years’ War. It is a National Historic Site (Canada) and an IEEE Milestone.

Cabot Tower on Signal Hill. (Source: Wikimedia Commons.)

Computer History Museum

Address: 1401 N. Shoreline Blvd., Mountain View, CA

Website: http://www.computerhistory.org/

We’ve become so used to having a Dell or a Mac or a Chromebook handy that we sometimes forget that “computing” is a synonym for calculating — or, even more fundamentally, counting. The Computer History Museum reminds us that computing goes back a long way. Its collection of artifacts associated with the history of computing encompasses everything from the abacus, invented well over four millennia ago, to smartphones designed mere months ago.

This is one of the few places to go to get a comprehensive review of what can be achieved with steadily increasing computational power, with an emphasis on hands-on demonstrations. Recent special exhibits include an examination of the life of computing pioneer Ada Lovelace and demonstrations of autonomous vehicles.

One of the earliest computing devices, the abacus, on display at the Computer History Museum. (Source: Wikimedia Commons.)

Roosevelt Dam

Location: The Salt River, northeast of Phoenix, AZ

Website: https://www.nps.gov/articles/arizona-roosevelt-dam-and-powerplant.htm

In 1911, Roosevelt Dam was the first dam to be completed under the Newlands Reclamation Act of 1902. The aim of the Act was to irrigate the southwestern United States, but an inadvertent consequence of the Roosevelt Dam’s siting helped usher in the era of federal generation of electricity and megahydroelectric dams.

Roosevelt Dam was remote, and hauling in fuel oil was arduous, so the builders decided to build a hydroelectric plant on site. The first plant was small enough to tuck into a shallow cave in the canyon wall, but by 1909, engineers had built a new facility and shipped in three 1,000-kW generators. The excess electricity was transmitted to the Salt River Valley, including the growing town of Phoenix, Arizona.

The success of the Roosevelt Dam paved the way for subsequent, larger, and far more well-known hydroelectric plants such as the Hoover Dam and the Bonneville Dam. The original masonry dam was named a National Historic Landmark. A mid-century renovation encased the original dam in concrete.

The Roosevelt Dam was a pioneer in hydroelectric plants for federal electrification. (Source: Wikimedia Commons. Photographer: Nicholas Hartmann.)

VintageTEK

Address: 13489 SW Karl Braun Drive, Beaverton, OR

Website: https://vintagetek.org/

Just as Hewlett-Packard was the foundation of a technology hub in Palo Alto, Tektronix established Portland as a technology center. A smaller tech hub, to be sure, but Tek inspired as much affection in Oregon as the old HP did in California.

Two former Tek engineers opened VintageTEK in 2011. Currently housed in a former manufacturing facility on the Tektronix campus, VintageTEK tells the story of a company that did not invent oscilloscopes but became almost synonymous with the devices after introducing a series of innovative refinements over several decades.

Exhibits at VintageTEK include “a vast number” of restored and operating Tek products, early photographs of the company and its employees, and training and demonstration historical films and videos. The non-profit operation hosts tours and demonstrations for local schools. It’s open to visitors two days a week.

Some of the earliest Tektronix equipment on display on the VintageTEK photo tour. (Source: Vintagetek.org.)

Fermilab

Address: Kirk Road and Pine Street, Batavia, IL

Website: http://www.fnal.gov/

Still one of the premier working laboratories for high-energy physics research, Fermilab was established in 1967 as the National Accelerator Laboratory. In 1983, the lab finished construction on the Tevatron, which provided the data that led to the discovery of the top quark in 1995. The Tevatron was shut down in 2011, but Fermilab still conducts research into some of the strangest of physical phenomena, including dark matter, neutrinos, and other subatomic particles.

The lab is set up for self-guided tours and presents a lecture series along with the once-a-month Ask-a-Scientist forum. It also hosts a frequent series of barn dances, folk dances, and English country dances. Attached to the lab is the Lederman Science Center , which offers science exhibits, activities, and formal classes geared toward young students and families.

The 300-ton NOvA neutrino detector at Fermilab . (Source: Fermilab.)

Alexander Graham Bell laboratory

Address: 5 Exeter Place, Boston, MA

No official website

“Mr. Watson, come here! I want to see you” is one of the most famous utterances in science history, ranking right up there with Archimedes’ (apocryphal) yelp of “Eureka!” It was the message from Alexander Graham Bell to his laboratory assistant Thomas Watson on March 10, 1876 .

The first intelligible voice communication by wire was accomplished in an upstairs laboratory in an unremarkable building on an unremarkable street in Boston. Perhaps fittingly, the achievement goes unremarked anywhere in the neighborhood.

Visitors can walk by, but the building is a private residence. If anyone is interested in making an offer, by the way, it’s probably worth about $4.3 million, according to the real estate experts at Zillow.

The early Bell Labs, at 5 Exeter Place, Boston. (Source: Zillow.)

Got your own favorite site associated with science history? Share it in the comments section.

Advertisement

Learn more about Electronic Products Digital