In some parts of the world, the average person uses more than 300 liters of water a day, but aboard the International Space Station (ISS), water is a limited and expensive resource. Since there's sectional storage space and no continuous supply, each crewmember is allocated about 2 liters of water daily. Astronauts have no choice but to take things to the extreme, meaning they must collect and reuse wastewater, recycling it from the moist breath exhaled by the crew and even from their own urine.

Before the Space Shuttle stopped flying in 2011, one of its uses was to supply water to the ISS by combining oxygen and hydrogen from the fuel cells on board. This produced enough water to fill up water storage tanks, but since there are no longer regularly scheduled deliveries of water to the ISS due to high cost, astronauts must rely on recycling the limited amount they have to drink, cook, wash themselves and conduct science experiments.

“Right now on the ISS they primarily use distillation, that's like boiling the water, and that treats all the urine,” said Michael Flynn, lead scientist of the NASA Ames Research Center's Water Technology Development Laboratory. When boiling the water the urine turns to steam, which is essentially clean, except for small traces of ammonia and some other gases. This rises into a distillation chamber, leaving behind impurities and salts, which are discarded. Once the steam is cooled, it condenses back to liquid.

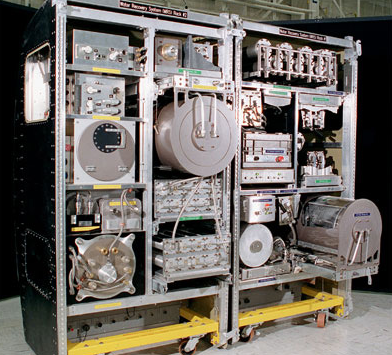

The ISS water-recycling system that generates potable water after treating urine and condensate water. Courtesy of NASA.

“Then the humidity condensate, which is the water that's in your breath, is condensed out of the atmosphere and that goes through a unit called a multi-filtration bed, which is basically a lot of chemical absorbents,” Flynn said.

The product of the multi-filtration bed and the distillation system are combined together before going through a catalytic oxidizer, a device with a bed full of catalysts.

“You add a little bit of heat and a little bit of oxygen and that serves as a dual purpose of oxidizing any trace contaminants that may be in the water, and also insuring that the water is sterile,” Flynn said.

According to Flynn, there are also water-recycling technologies inspired by life in space being used on Earth.

“We currently have a 250-person office building at Ames Research Center that's using a next-generation NASA life support water-recycling system,” he said. “It's not exactly the same as is on ISS, slightly different. It would be a system that is being developed for a Mars exploration mission.”

The building, Sustainability Base, also called the Green Building, was constructed by NASA Ames and is known to be one of the greenest buildings in the federal government. It uses a next-generation system that NASA is currently developing called Forward Osmosis. Though this technology has been around since the 1960s, according to Flynn, it's a big new area in water recycling, and NASA's system is one of the first larger-scale forward-osmosis systems being developed.

“It uses a membrane-based system and what's unique about that system is that one of the things that really prevents terrestrial water recycling deals with two things,” Flynn said. “One is the need to have double plumbing in the building, so that would mean that you collect, for instance, hygiene water and water from the toilet separately.” Obviously, there would be a human health issue recycling toilet water directly into potable water, but according to Flynn, what comes out of the sink and shower isn't inherently hazardous, so it makes a good source to treat for water recycling.

“The other element that's really important with regard to the Green Building is that at least in the state of California, right now there is not a permitting agency,” said Flynn. “If you wanted to build a building and you want to recycle water inside the building, there is no state of California organizations you can go to that will provide you with a permit to do it and provide you with guidance as to what's appropriate and what's not.”

Recently NASA has devised its own own permitting mechanism in order to provide a demonstration for the state of California and other states.

“They could see an example of a permitting process that has been implemented, they could see the results of that permitting process needing operation for prolonged periods of time, and they could use that as at least a starting point for developing their own regulatory processes,” Flynn said.

Flynn (second from left) and other researchers next to a forward-osmosis water-recycling system. Image courtesy of NASA.

What NASA brings to the table that's really unique is the ability to make water-recycling technologies very small and fully automated.

“The idea is that you could take a water-recycling system and put it into an existing building by just simply putting it under the counter area in the bathroom, or putting it in a closet outside of the bathroom,” Flynn said. “It doesn't require new construction.”

Over the years NASA has put a lot of time and money into technology development for water recycling. Flynn said there haven't been many changes to water-recycling technologies aboard the ISS because they've proven to be very successful. As water is crucial to the survival of astronauts living and working in space, and with ideas of traveling further from Earth, NASA is still working on ways to rapidly recycle this precious commodity.

“I can tell you there have been times on ISS where they had to make a decision, do we launch water to ISS or do we launch propellant?” Flynn said. “Fuel, which if the ISS gets too low, it'll de-orbit, or water? And the decisions have been water.”

Want to go behind the scenes with NASA? Littelfuse has created an Exploration & Discovery Experience for the engineering community as part of its 2013 Speed2Design program. Winning design engineers will get the opportunity to spend time with NASA engineers at two NASA facilities and learn about the latest in space technology. For more information and to enter, visit speed2design.com.

Advertisement

Learn more about LittelfuseNasa