The above video epitomizes technology of the 80s. The blinking cursors, the green typeface on the screen, and the largeness of the PC evoke nostalgia for even kids who were born in the 90s.

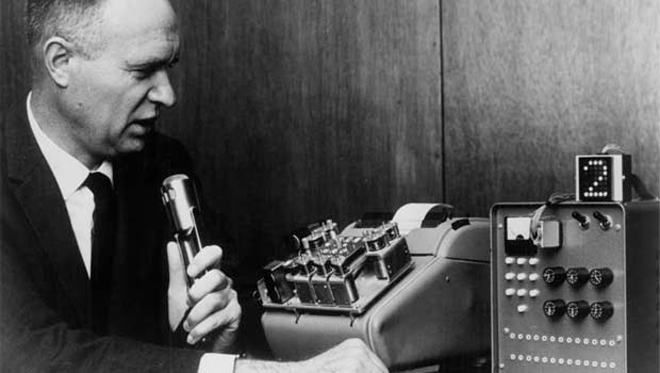

IBM’s idea for vocal interactive software predated Apple’s concept of Siri. Big Blue released an array of tech products that hoped to help businesses with the everyday processes they conducted. In the 1960s, IBM’s Shoebox could compute simple mathematical equations and respond to vocal commands. Following Shoebox, IBM released a talking typewriter in 1980.

Image of IBM's Shoebox

It was 1986 when IBM first introduced its speech recognition technology in a purchasable, concrete, and tangible form. The innovation recognized human speech, isolating each word from the next. It was programmed to comprehend words that were spoken slowly. In 1992, IBM’s speech recognition system evolved into the Speech Server Series, aiding businesses to quicken the dictation process.

Having a vocabulary of over a few thousand words, the device could also establish the difference between homophones like “there,” “their,” and “they’re.” IBM needed specialized hardware to run the appropriate algorithms in order for speech recognition technology to work. With the extremely limited PC resources available in the 80s, this was a difficult task to tackle.

On each computer, four custom “Albert” cards were intrinsic. The cards’ name paid homage to Albert Tangora, who had set the world record for the fastest typist in the 80s. The Albert cards contained ample memory to hold the entire speech recognition model. The machine would first locate spoken words, and then fine-tune accordingly to learn the person’s voice for easy understanding.

In our modern era, Siri has cornered the market on vocal recognition, and while the dictations aren’t always understood, Siri still does a good job. When we ask Siri a question, and receive lists for the answer, we realize that Siri is not precisely accurate and that computers are not always right. Our interactions with Siri still make us realize that no matter how well we program computers to be, they are still not human.

Advertisement

Learn more about Electronic Products Magazine