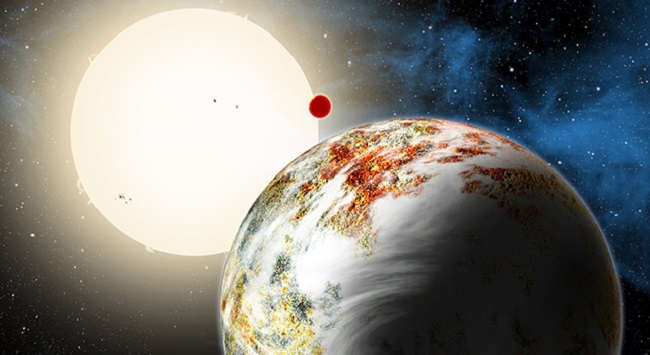

NASA astronomers recently discovered a new class of rocky planet measuring 2.3 times the size of Earth and 17 times its diameter. Dubbed “mega-Earth,” this type of planet challenges all previous conventions of planetary formation.

Dubbed Kepler-10c after the agency’s Kepler telescope that spotted it, the planet exhibits a hard surface very similar to that of Earth’s. But unlike Earth, Kepler-10c orbits a sun-like star every 45 days, making it far too warm to sustain life (as we know it). The star is located 560 light years away in the Draco constellation, and also hosts the Kepler-10b, the first Earth-like rocky planet found outside our solar system.

Kepler-10c was first discovered after a change in luminosity taking place in front of a parent star indicated the presence of a planet in orbit. The same technique is used to determine a celestial body’s diameter, and found that Kepler-10c measured 29,000 km. Mass was observed with the assistance of the Harps-North instrument on the Telescopio Nazionale Galileo in the Canary Islands; examining the gravitational interaction between the planets and host stars revealed a mass 17 times greater than that of Earth’s.

These findings left the scientific community baffled and confused, indicating that Kepler-10c was something of an anomaly. It was historically believed that mass this large was a trait exclusive to gas giants, because planets this large naturally draw enough hydrogen onto themselves and eventually wind up resembling something like Neptune or Jupiter. Yet, Kepler-10c’s diameter specified the planet was solid.

“Kepler-10c is a big problem for the theory,” astronomer Dimitar Sasselov, director of the Harvard Origins of Life Initiative, told Discovery News. “It’s nice that we have a solid piece of evidence and measurements for it because that gives motivations to the theorists to improve the theory,” he said. But unfortunately, scientists are unsure how mega-Earths form nor why no such planet exists between the largest rocky planet in our solar system, Earth, and the smallest gas giant, Neptune.

More confounding yet is the suggestion that Kepler-10c’s host star is 11 billion years old; if the star formed during the early days of the universe, how could a planet as dense as Kepler-10c form if the other exploding stars have not yet had time to create the elements needed to construct such a rocky planet? Recall that new elements are created at the end of a star’s life cycle yet not enough time has elapsed to theoretically permit the formation of Kepler-10c. Its very existence implies that rocky planets may have actually formed earlier in cosmic history than previously thought and older star systems should not be ignored in the search for life.

Via NASA, DiscoveryNews, BBC

Advertisement