Humanity has a complex and contradicting relationship with sharks. On one end, sharks are demonized as apex predators and hunted for sport, while on the other, they are the favorite subject of many biologists and animal lovers alike; there’s even an annual television block devoted to shark worship. Yet, for all our fancy sensors and underwater drones, we remain baffled over some very basic shark behavior. How do sharks move when pursuing prey? Do they avoid other species? A team of biologists from the Hawaii Institute of Marine Biology and the University of Tokyo’s Atmosphere and Ocean Research Institute have set out to answer many of these questions using a very popular consumer electronic device: the strap-on camera.

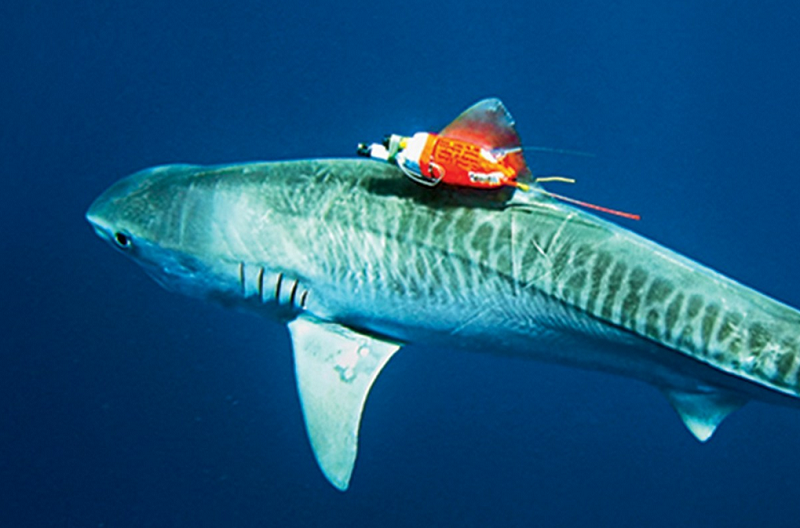

The researchers have joined forces with the Japanese data-logging firm obnoxiously named Little Leonardo, to build a special kind of camera that’s small enough to discretely attach to the shark’s fin and remain safety secured without disrupting the 420-million-year-old creature’s natural underwater grace. The camera uses a triaxial accelerometer-magnetometer, much like a flight-data recorder, and automatically releases from the fin after a period of two weeks. Once this occurs, the camera conveniently floats to the water’s surface and broadcasts its coordinates to the researchers for pick-up.

Click below to check out some of the recorded footage, which in the words of ecologist Carl Meyers, is simply astounding.

The video displays Hawaiian sandbar sharks, hammerhead sharks, and blacktip reef sharks diving in close formation while the sandbars chase around females of their species. “This is the first-ever shark’s-eye view,” says Meyer. The researchers have never before seen sharks of multiple species flocking and socializing. “Until we deployed the cameras, we had no idea that these mixed-species shark aggregations were occurring only a few miles from our research institute.” Perhaps the new knowledge stemming from this research will help eliminate some of the stigma surrounding the animals that directly contributes toward their overhunting.

Via Wired

Advertisement

Learn more about Electronic Products Magazine