Thanks to a series of recent technological advancements, today’s homeowner might soon power their houses with the same solar cell technology used in space.

“Concentrating photovoltaic (CPV) systems leverage the cost of high efficiency multi-junction solar cells by using inexpensive optics to concentrate sunlight onto them,” explained Noel C. Giebink, an assistant professor of electrical engineering, Penn State, who worked with an international team of researchers on a more user-friendly form of this technology. “Current CPV systems are the size of billboards and have to be pointed very accurately to track the sun throughout the day. But, you can't put a system like this on your roof, which is where the majority of solar panels throughout the world are installed.”

Giebink pointed out that the falling cost of today’s silicon solar cells is making them a smaller fraction of the overall cost of solar electricity, which includes things like permitting, wiring, installation, maintenance, and other “soft” costs. Improving the efficiency of solar cells from the 20% that silicon presently offers to the 40% that multi-junction CPVs can offer is important because the increased power it generates will, in turn, reduce the overall cost of the electricity it generates.

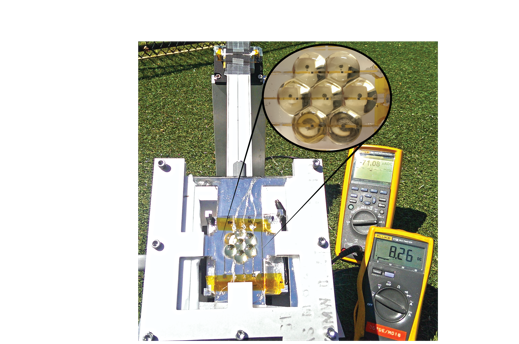

In order to place CPV technology on rooftops, the researchers combined miniature, gallium-arsenide photovoltaic cells, 3D-printed plastic lens arrays, and a moveable focusing mechanism to reduce the size, weight, and cost of the current system.

“We partnered with colleagues at the University of Illinois because they are experts at making small, very efficient multi-junction solar cells,” said Giebink. “These cells are less than 1 square millimeter, made in large, parallel batches and then an array of them is transferred onto a thin sheet of glass or plastic.”

The group’s efforts were published in the February 5th edition of Nature Communications. In it, the team reports that in order to focus sunlight on the array of cells, they embedded them between a pair of 3D-printed plastic lenslet arrays. Each lenslet in the top array acts like a small magnifying glass, and is matched to a lenslet in the bottom array that functions like a concave mirror. Having every solar cell located in the focus of this duo allows for the sunlight to be intensified more than 200 times. And because the focal point moves with the sun over the course of the day, there’s a middle solar cell sheet in there that tracks its movement by sliding laterally in between the lenslet array.

This solution enables efficient solar focusing for a full eight hours a day with only about 1 centimeter of total movement needed for tracking.

Worth noting, the team lubricated the sliding cell array and also improved transmission through the lenslet sandwich by using optical oil, which allows small motors using a minimal amount of force for the mechanical tracking.

“The vision is that such a microtracking CPV panel could be placed on a roof in the same space as a traditional solar panel and generate a lot more power,” said Giebink. “The simplicity of this solution is really what gives it practical value.”

The total thickness of the panel is about a centimeter, and about 99% of it, which is everything except for the solar cells and their wiring, is made up of acrylic plastic or Plexiglass.

Translation: this could be an inexpensive technology to produce.

Giebink does, however, caution that CPV systems are no suitable for all locations.

“CPV only makes sense in areas with lots of direct sunlight, like the American Southwest,” he said. “In cloudy regions like the Pacific Northwest, CPV systems can't concentrate the diffuse light and they lose their efficiency advantage.”

Giebink’s team tested their prototype out over the course of a day in State College, Pennsylvania. While the printed plastic lenses weren’t exactly up to specification, they were able to report over 100 times solar concentration.

Advertisement

Learn more about Electronic Products Magazine