Researchers at the Georgia Institute of Technology have created a system that is capable of teaching people Morse code within four hours using a series of vibrations felt near the ear.

After being exposed to the system for this time frame, participants were 94% accurate keying a sentence that included every letter of the alphabet; they were 98% accurate writing codes for every letter.

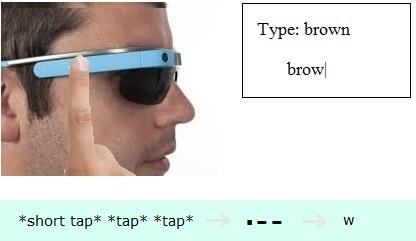

Participants wore Google Glass devices and learned the code without paying active attention to the signals; instead, they played games while feeling taps and hearing the corresponding letters.

It’s the latest advancement in the developing field that is passive haptic learning (PHL). The same method (using vibrations while participants aren’t paying attention) has taught people braille, how to play the piano, and improved hand sensation for people who’ve suffered a partial spinal cord injury.

The Georgia Tech team decided to use Glass because it is equipped with both a built-in speaker and tapper (the device’s bone-conduction transducer).

During the study, participants were tasked with playing a game while feeling vibration taps between their temple and ear. These taps represented the dots and dashes of Morse code and served to passively teach users through their tactile senses, even while they were distracted by the game.

The actual taps were created when researchers sent a super low-frequency signal to Glass’s speaker system. Measuring in it as just 15 Hz, the signal was far below the hearing range; however, due to it being played very slowly, it felt somewhat like a vibration.

Half of the participants felt the vibration taps and heard a voice prompt for each corresponding letter; the other half, marked as the control group, felt no taps to help them learn. During the course of the study, participants were tested on their knowledge of Morse code and their ability to type it. At just around the four-hour mark, a final test was administered, whereupon everyone was asked to type the alphabet in Morse code.

The control group was accurate half the time. Those who felt the passive cues were close to perfect.

“Does this new study mean that people will rush out to learn Morse code? Probably not,” said Georgia Tech Professor Thad Starner, who led the study. “It shows that PHL lowers the barrier to learn text-entry methods — something we need for smartwatches and any text-entry that doesn't require you to look at your device or keyboard.”

Previous PHL studies used custom hardware to provide tactile stimuli; noteworthy in this case is the use of existing hardware.

“This research also shows that other common devices with an actuator could be used for passive haptic learning,” Starner added. “Your smartwatch, Bluetooth headset, fitness tracker, or phone.”

“In our braille and piano PHL studies, people felt vibrations on their fingers, then used their fingers for the task,” explained Ph.D. student Caitlyn Seim, who worked with Starner on the project. “This study was different and surprising. People were tapped on their heads, but the skill they learned was using their finger.”

Looking ahead, the Georgia Tech team plans to look into whether PHL can teach people how to type on a QWERTY keyboard. It’s expected to be a difficult endeavor, as several letters will need to be assigned to the same finger; this, as opposed to Morse code, which uses just one finger.

Advertisement

Learn more about Electronic Products Magazine