When Open Source Instruments selected a circuit board assembly house based on proximity—rather than electing to ship parts across the country to Advanced Assembly—they found themselves in a situation in which they were $20,000 in the hole and faced with an outrageous amount of time spent fixing the problem.

Headquartered in Waltham, Massachusetts, Open Source Instruments designs and develops devices that are implanted into lab animals to detect and monitor epileptic activity via electroencephalograms (EEGs). These devices are part of research studies to work on finding therapeutic drugs to treat pre-existing epilepsy in children and adults.

While the engineering team at Open Source Instruments works on three to five products each year, one of their current projects is a subcutaneous transmitter (SCT). This SCT is comprised of a circuit board encapsulated in epoxy, a battery, a power connector to calibrate the RF transmitter and an exterior silicon layer. Once built, the device is implanted into a lab rat or mouse for up to 20 weeks of research.

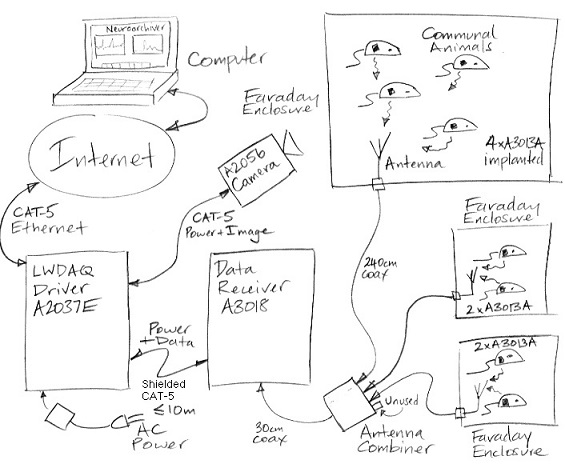

Figure 1: A subcutaneous-transmitter system showing three faraday enclosures. One is large, approximately 2 square meters, containing four rats, each with their own implanted transmitter. Two smaller enclosures contain rats and mice in isolated cages.

Figure 1: A subcutaneous-transmitter system showing three faraday enclosures. One is large, approximately 2 square meters, containing four rats, each with their own implanted transmitter. Two smaller enclosures contain rats and mice in isolated cages.

According to Kevan Hashemi, the President of Open Source Instruments, “We’re forging ahead into the unknown, developing new instruments for those willing to collaborate on experiments with us. While the cost of our product is roughly 30 percent that of competitive products, cost is not the most important factor. It’s spending three years getting an experiment to work and someone’s career depends on it. We’re the only provider today that willingly and honestly discusses the frequency response of the EEG amplifier, or reception reliability with our customers.”

Within the research community, this information is critical to scientific projects fraught with a number of inherent challenges.

Breaking Through Research Barriers

For customers of Open Source Instruments, the failure of the transmitter can be expensive in terms of time and money, but perhaps most importantly in a lack of results. For example, in the case of the SCT, each device is worth approximately $500 and researchers spend two hours implanting the transmitter into an animal. Once the device has been implanted and begins transmitting, the eight-week monitoring period starts. Depending on the results of this initial trial, an additional monitoring period of twelve weeks may be required.

Attempting to eliminate the possibility of failure is at the forefront of Open Source’s product development. To ascertain the possibility of humidity corrosion in a circuit, and when it might likely fail, circuits are poached in water while they run at 60 °C. Taking the results of this simulation and multiplying them by ten, they are able to determine if the boards can withstand the 20 week research project.

Concerns, however, aren’t limited to humidity corrosion. Power consumption considerations are just as important. While the device is turned off it only requires a 2 microamps compared to the 80 microamps it consumes when being used. As a result, the board must be extremely clean and remain untouched during assembly so that there is no oil residue. Once encapsulated in epoxy, chemical reactions would compromise the resistance of the components.

Open Source Instruments relies heavily on their relationship to board assembly providers and began working with Advanced Assembly approximately 10 years ago. In the early days, to produce 20 printed circuit boards, Open Source was required by other companies to purchase their parts on complete reels – an unnecessary investment of thousands of dollars. In contrast, Advanced Assembly told Hashemi he could save money and simply send them the parts in loose format and only the quantity needed.

“They got me with the loose parts thing—that was completely unprecedented,” said Hashemi. “They would proceed to take them out of the bag, use their proprietary systems and processes to place them onto a board. I realized that these guys obviously have some very smart people there, who have designed some ingenious machines. No one else had ever said ‘Oh, just send them in a bag and it will be okay.’”

There are several reasons that the relationship progressed from there and a major one was the critical nature of time. When Open Source delivered BOM and Gerber files, a quote from Advanced Assembly consistently followed within 24 hours instead of a week or more—a time frame Hashemi noted he’d often faced when dealing with other assembly companies.

Open Source eventually used Advanced Assembly’s turnkey services. After calculation, Hashemi figured it would cost only $50 more on a $2,000 part order to do turnkey—a logical investment.

“At one point, we thought it would be important to do business closer to home instead of shipping parts to Advanced Assembly in Colorado. We talked to rep from a local company, and unfortunately, that situation led to disaster. It cost us $20,000 to recover from the cracked capacitors loaded by machines that were improperly calibrated for the height of the capacitors,” he said.

When it comes to the exact layout of the components, the spacing between them and the board, the potential solder-based issues and insisting upon consistent communication, Open Source Instruments admits to being a demanding customer. And, if there’s a failure for any reason, Open Source Instruments wants to discuss as many hypotheses as necessary to find the source of the problem.

“Advanced Assembly provides us a quote in 24 hours; they’re very responsive; and their prices are extremely competitive. They’re all about solving problems and challenges. Advanced Assembly’s work is as good as or better than any other manufacturer we have used, but their service is better,” added Hashemi.

By: Carolyn Mathas

Advertisement

Learn more about Advanced Assembly