A new study shows that automated “artificial pancreas” systems could be available in as little as two years, helping to reduce the daily self-care regiment that those with type 1 diabetes must maintain. Current treatment processes for type 1 diabetes include monitoring blood glucose levels with a fingerstick blood test and, if needed, using an insulin pump to lower high glucose readings. The goal of the artificial pancreas is to combine these procedures into one “closed-loop” system.

This combined system would involve a needle under the skin constantly tracking blood glucose levels and automatically administering insulin to the body. Because of patients’ varying insulin requirements, an automatic system would be aware of bodily fluctuations and fix itself to pump what is needed. Studies have shown that these closed-loop systems are successful in maintaining an ideal glucose range in patients’ bodies, and have been able to shorten the time patients spend in a hypoglycemic state, which is when the body suffers from low blood sugar.

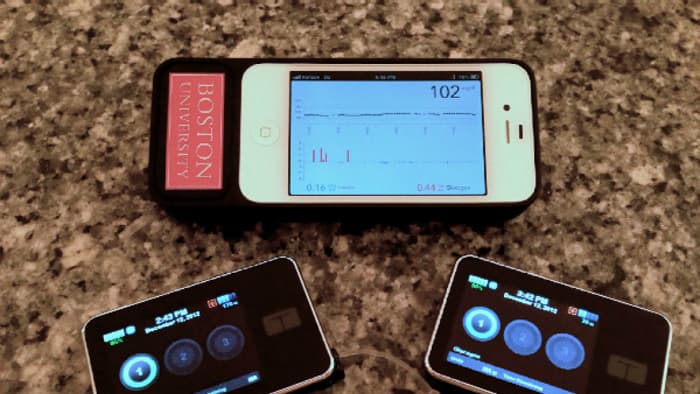

Among the testing systems is a bionic pancreas, which, as of June 2014, was being developed by scientists at Boston University (BU) and had performed better than expected in tests. When using the device, adults required 37% fewer interventions for low blood glucose. “A cure is always the end goal,” said BU’s Dr. Ed Damiano around the time of these trials. “As that goal remains elusive, a truly automated technology, which can consistently and relentlessly keep people healthy and safe from harm of hypoglycemia, would lift an enormous emotional and practical burden from the shoulders of people with type 1 diabetes.”

Appearing in clinical trials at diabetes camps and outpatient settings, artificial pancreas systems seem to be more viable than transplants of either the entire pancreas or beta cells that run insulin production. Those types of surgeries may be prone to failure, thus causing more complications for a patient. “In trials to date, users have been positive about how the use of an artificial pancreas gives them ‘time off’ or a ‘holiday’ from their diabetes management since the system is managing their blood sugar effectively without the need for constant monitoring by the user,” said the research paper’s authors.

With optimistic feedback on its side, the artificial pancreas still has room for some improvements. Currently, the time that insulin takes to reach peak levels in the bloodstream is slow, stirring up a need for faster types of insulin in the device. While final adjustments are being made, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) is reviewing a system proposal that could be approved by next year. Reports also hint that, in the U.K., the closed-loop systems could be available by late 2018.

Advertisement

Learn more about Electronic Products Magazine