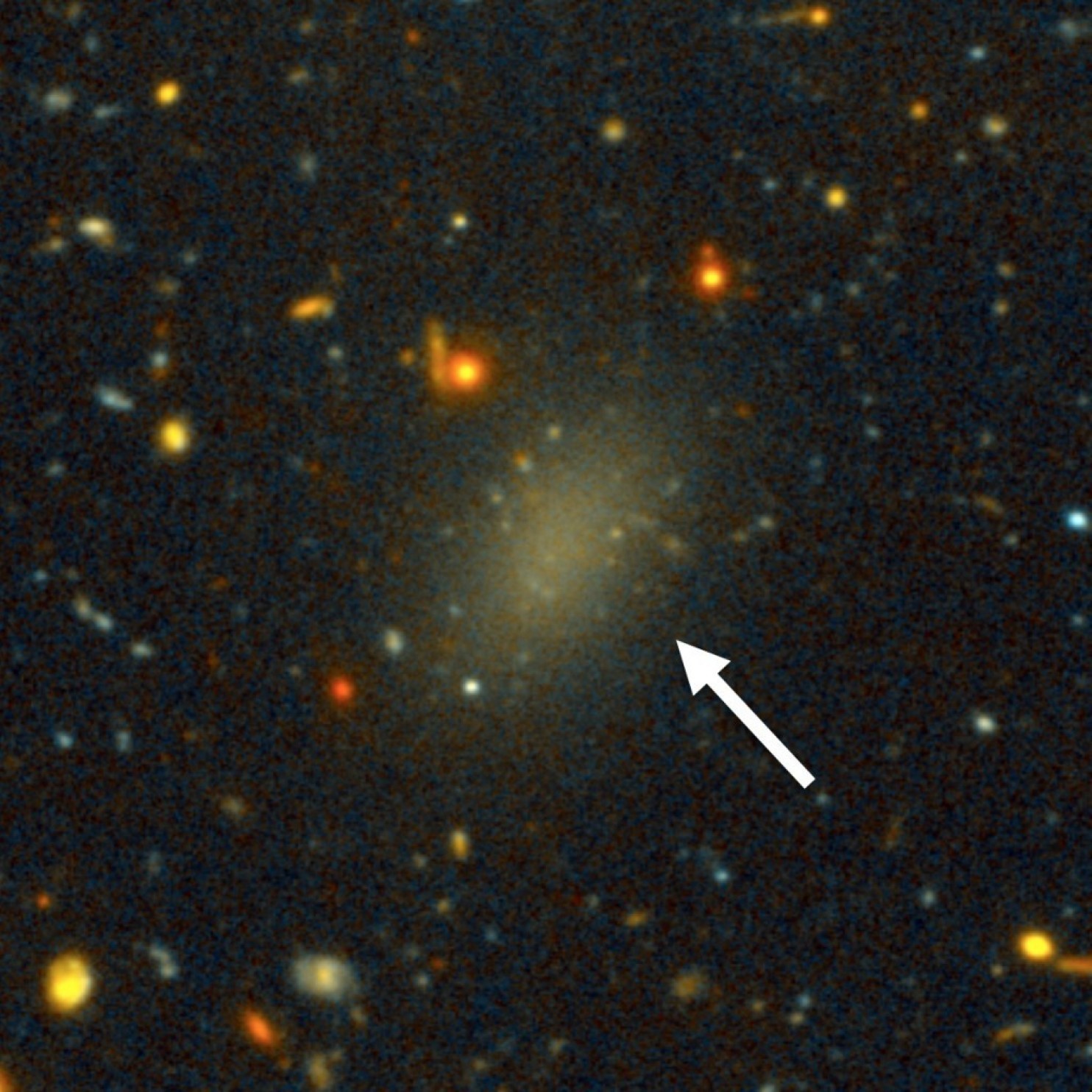

Save for its gravitational influence, little is known of the tenebrous cloak of dark matter enveloping much of the universe that is not void. The elusive substance remains unobservable, though its effect on the cosmic microwave background implies it out-masses normal matter by a ratio of five-to-one all across the universe. Now, cosmologists have discovered a galaxy possessing the same mass distribution as our Milky Way, but with only 1% of its star power — the remaining 99% of its mass is made up of dark matter, defying all known understanding of how galaxies form.

Scientists believe that the newly discovered galaxy — dubbed Dragonfly 44 — is one of many; finding one closer to home could help provide the first direct detection of dark matter.

A team made up of astronomers from Yale University, and the University of Toronto discovered Dragonfly 44 using a telescope built from camera parts. Telephoto lenses, like the kind used in nature and sports photography, provided a means of spotting the kind of large and dimly-lit objects that are problematic for standard telescopes.

“We planned to study the outskirts of galaxies to see what exists around them, but by accident, we saw all these little smudges,” study author Pieter van Dokkum of Yale told the Washington Post. The observation was so unlike anything previously detected, that van Dokkum and his colleagues assumed it was an error. Upon further inspecting the raw data, the team was amazed to find that they stumbled upon a whole new class of object.

The resulting anomaly matched the Milky Way in size, but lacked the number of stars otherwise needed to sustain its mass; in no way could the diffuse matter observed supply enough gravitational force to contain the mass and prevent the galaxy from tearing apart. The only logical explanation was that dark matter must be the force holding everything together.

No previously discovered dark galaxy comes even remotely close to the size of Dragonfly 44. “They are so diffuse, these galaxies, so tenuous, that they would be ripped apart. There just wasn’t enough mass to hold them together,” van Dokkum said.

Prying through the data revealed that the number of stars possessed by Dragonfly 44 differed from those of the Milky Way by a factor of 100, with the remaining dark matter spread uniformly throughout the galaxy. Ordinarily, dark matter clusters in specific regions and accounts for less than half of the star-filled central regions.

The fact that Dragonfly 44 resembles our galaxy in size — which is a very average-sized galaxy — and not some unusually large galaxy suggests that perhaps such formations are not quite as unusual as we’d expect. If this turns out to be fact, then our entire fundamental understanding of cosmology stands to alter.

“We thought that that ratio of matter to dark matter was something we understood. We thought the formation of stars was kind of related to how much dark matter there is, and Dragonfly 44 turns that idea on its head,” van Dokkum said.

At the end of the day, Van Dokkum and his team are hopeful that we are standing on the precipice of an entirely new class of object and not some singularly odd galactic formation. They hope to detect even darker galaxies someday, or maybe even some made up entirely of dark matter.

Source: Washington Post

Advertisement

Learn more about Electronic Products Magazine