When a microstimulator and geomagnetic compass were attached to the brains of blind rats, researchers found that the rodents learned to use new information about their location, and navigate through a maze nearly as well as normally sighted rats.

This discovery suggests that a similar kind of neuroprosthesis for humans might one day help the visually impaired walk freely through the world.

One of the highlights from the study was the details surrounding the remarkable flexibility of the mammalian brain.

“The most remarkable point of this paper is to show the potential, or the latent ability, of the brain,” says Yuji Ikegaya of the University of Tokyo. “That is, we demonstrated that the mammalian brain is flexible even in adulthood — enough to adaptively incorporate a novel, never-experienced, non-inherent modality into the pre-existing information sources.”

Ikegaya went on to explain that the brains of the animals they studied were ready and willing to fill in “the ‘world’ drawn by the five senses” with a new sensory input.

It’s worth noting that it was never the intention of Ikegaya and his colleague Hiroaki Norimoto to restore vision; rather, they wanted to restore the blind rats’ allocentric sense. For those unfamiliar, the allocentric sense is what allows animals and people to recognize the position of their body within the environment. Ikegaya and Norimoto wanted to know what would happen if the animals could “see” a geomagnetic signal. Specifically, would this signal fill in for the animals’ lost sight, and would the animals know what to do with the information?

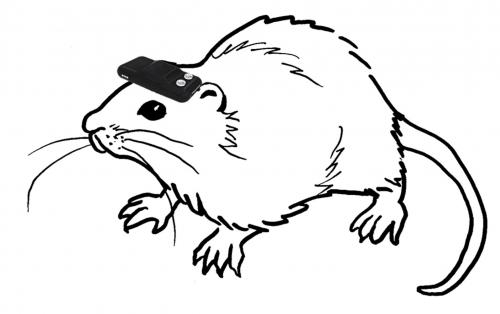

The head mountable device the researchers developed allowed them to connect a digital compass (similar to that found in a smartphone) to two tungsten microelectrodes for stimulating the visual cortex of the brain.

The device, which was light enough so as to not impose upon the rats’ movement, also allowed the researchers to turn the brain stimulation up and down, and included with it a rechargeable battery.

When attached to the rat, the geometric sensor automatically detected the animal’s head direction and generated electrical stimulation pulses indicating which direction they were facing, (e.g. north, south, west, east).

During the actual testing phase, the rats were trained to seek food pellets in a maze. After a few dozen trials, the researchers say the animals learned to use the geomagnetic information to solve the mazes.

What’s more, the rats’ performance levels and navigation strategies were on par with those of normally sighted rats.

Ikegaya and Norimoto reported that the animals’ allocentric sense was restored.

“We were surprised that rats can comprehend a new sense that had never been experienced or 'explained by anybody' and can learn to use it in behavioral tasks within only two to three days,” Ikegaya says.

In terms of human applications, the researchers suggest a relatively simple application: attach geomagnetic sensors to the canes used by visually impaired people to help them get around.

Speaking a bit more broadly, Ikegaya and Norimoto say that based on these findings, humans could expand their sensors vis-à-vis artificial sensors that detect things like geomagnetic input, ultraviolet radiation, ultrasound waves, and more. They conclude that the human brain is capable of much more than what our limited senses allow.

“Perhaps you do not yet make full use of your brain,” Ikegaya says. “The limitation does not come from your lack of effort, but it does come from the poor sensory organs of your body. The real sensory world must be much more 'colorful' than what you are currently experiencing.”

Via eurekalert.org

Advertisement

Learn more about Electronic Products Magazine