While the internet is the most wide-reaching communication tool ever unveiled, it’s also a machine filled with biases that could be a hazard to the future. According to a study conducted over a year-long period from Stanford researchers, the inability of young students to decipher between “fake news” and real news is “dismaying” and a “threat to democracy.”

Stanford drew these conclusions after having more than 7,800 middle school, high school, and college students evaluate articles, tweets, and comments. Eighty percent of middle schoolers were not able to differentiate “sponsored content” from articles; more than 80% of high schoolers accepted the validity of photographs without verification; and high school students couldn’t tell fake news from real news on Facebook. What’s most disheartening is that the members of the first generation are often referred to as “digital natives.”

“There's just so much information, it's harder and harder to accurately and effectively process it,” said Yalda Uhls, a child psychology researcher and author of Media Moms and Digital Dads: A Fact not Fear Approach to Parenting in the Digital Age .

Our brains use heuristics, or the “rules of thumb,” to make a decision that we believe is simple or must be made quickly. However, those shortcuts don’t always lead to the best results. For example, if you’re on one end of the political spectrum and a headline confirms what you already believe, your brain will take that shortcut.

Additionally, there aren’t enough gatekeepers to fact-check or edit news that is delivered. Anyone can create a website, and there’s no turning off news. With Facebook feed, your friends and family post news that is near impossible to ignore, boosting those signals. To question the legitimacy, you truly have to think about it.

If it’s difficult for adults to identify fake, incorrect, and partisan news, how exactly are children supposed to?

“You have [writers] very skilled at their craft. Putting them up against 11-to-13-year-olds isn't fair,” said Jacob Deems, a teacher at the Academy of Global Citizenship, a public charter school in Chicago. “Students need to be taught [internet literacy] explicitly, but they also just need to grow up and mature.”

At what age should educators, both at home and in school, offer lessons to children on how to properly use the internet? In short, as soon as possible.

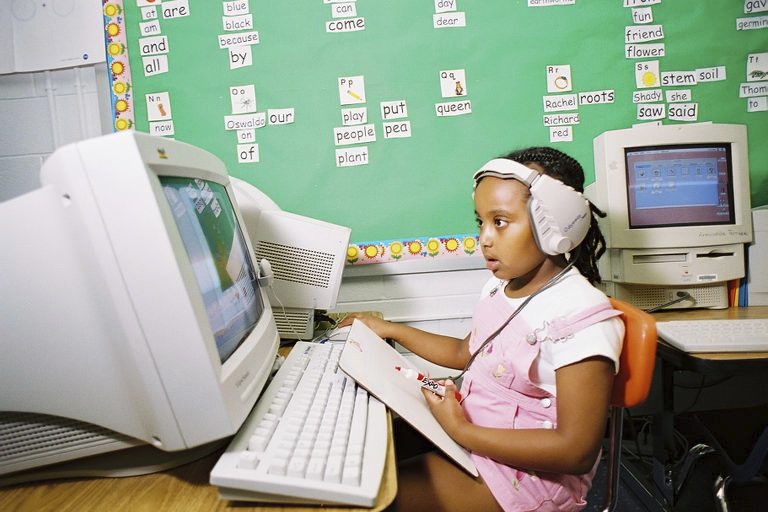

The internet is so prevalent in students’ lives before they even come to their parents. While they’re not navigating social media, they are using iPads as early as two, three, and four years old.

As part of Common Core standards, many schools are required to give lessons covering “digital literacy,” including how to surf the internet and navigate a computer, but also how to be a good “digital citizen.” The issue is that most teachers don’t give these types of lessons the same focus as they would with math and language.

“A lot of educators think [providing digital literacy] is not their job,” said Merve Lapus, director of school partnerships at Common Sense Media, a non-profit organization that provides technology and media education for children. “They think it's IT's job, or the teacher's special assistant, or the librarian. If it's only used in technology class, the lessons will only stay within technology class.”

Teachers who work to incorporate digital literacy into their classrooms do so through guides, interactive games, and lesson plans. These include articles with quizzes to promote reading comprehension, alerting children about security concerns on the internet, and breaking down the wall between real life and online in an attempt to eliminate cyberbullying.

If you’re taught at a young age to analyze the intentions of the outlet or the writer, you can sense their biases. One way to do this is to pull clips or articles from different sources and write down the purpose of the author and their point of view. An additional step to take is to inform students about how information gets to the reader in the first place, whether it be through news or ads. Children must learn that each time they click on something, they are creating a trail that brings information to them. It’s also useful that social media outlets, such as Facebook, are starting to view their role as media deliverers.

While the Stanford study was not exactly reassuring, it is important to know that if children are taught quality digital literacy lessons, they will be okay.

Source: Motherboard

Advertisement

Learn more about Electronic Products Magazine