By Heather Hamilton, contributing writer

An Australian research team is going where no one, save every 10-year-old, has gone before — ladies and gentlemen, the first real-life fart detector. The researchers recently unveiled an electronic pill designed to keep an eye on gas levels within the human digestive system. In combination with a receiver and mobile app, the capsule moves from the stomach to the colon, broadcasting gas-related developments as it travels. Previously, the researchers tested a similar capsule on pigs, expanding the study for use in humans.

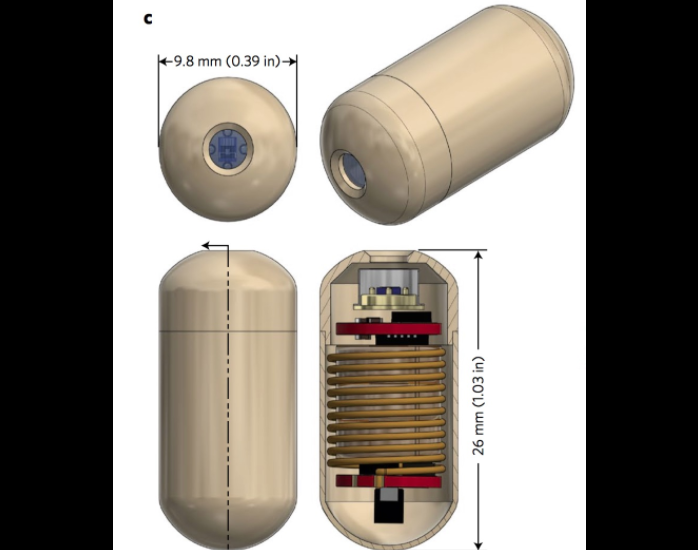

The pill is 26 mm in length and has a 9.8-mm external diameter, making it the size of many supplements on the market. It is surrounded by a polymer shell to control temperature, contains sensors for CO2 , H2 , and O2 , and has a silver oxide battery and transmission system. On one end, the capsule is gas-permeable to allow for quick diffusion of gases within the gut.

In Nature Electronics, Kourosh Kalantar-Zadeh of RMIT University and Peter Gibson of Monash University described their desire to understand the complex workings of the human gut, including specific conditions in each section, the role of microbes, and even the effects of certain foods on the gut.

“We found that the stomach released oxidizing chemicals to break down and beat foreign compounds that are staying in the stomach for longer than usual,” said Kalantar-Zadeh. Previously, the gut’s ability to react to foreign bodies was unknown.

Prior to the pill, such studies have been problematic because research required invasive procedures. The researchers noted in the journal article that they’re in the process of establishing a commercial company that can develop and test the capsules beyond the pilot program.

In the trial, the capsule was tested on six healthy people and monitored via ultrasound. It took 20 hours to move through the body, spending 4.5 hours in the stomach, 2.5 hours in the small intestine, and finally 13 hours in and through the colon, all the while measuring for gas. Researchers can identify gut process by looking at peaks and falls for CO2 , H2 , and O2 and comparing with what we currently know about gut bacteria.

The research team asked one participant to swallow the pill twice — once eating a high-fiber diet (50 grams/day) for two days and then again with two days of eating a low-fiber diet (15 grams/day). In the high-fiber scenario, the man passed the pill in 23 hours but experienced abdominal pain. The pill revealed elevated levels of O2 and fecal bacteria associated with poor gut health.

On a low-fiber diet, the pill took over three days to reappear, spending 13 hours in the stomach, 5.5 in the small intestine, and 54 in the colon, eventually requiring the man to take a high dose of fiber to initiate movement. Before the fiber, H2 levels drastically decreased, increasing again 12 hours after the fiber.

The remainder of participants took the pill on either a high-fiber diet (not as high as the aforementioned volunteer) or a low-fiber diet. The results were similar.

Researchers believe that this technology will lead to a more comprehensive understanding of the gut and gut health, eventually resulting in better medical treatment. While swallowing a sensor-laden pill may make some patients uncomfortable, it certainly offers a less invasive alternative to risky procedures and may soon become a routine part of medical evaluations.

“The data here — even though it was a very small cohort — are encouraging that smart, swallowable capsules can provide new insight into gastrointestinal goings-on,” said Giovanni Traverso, a gastroenterologist and biomedical engineer at Brigham and Women’s Hospital to Science News . “This really amplifies the field of ingestible sensors.”

Sources: Nature Electronics,Science News

Image Credit: Images courtesy of Rmit University

Advertisement

Learn more about Electronic Products Magazine