Using some surgical tubing and a bit of material found in Silly Putty, researchers at the University of California, Riverside Bourns College of Engineering, have created a new way to make lithium-ion batteries that last three times longer between charges compared to today’s standard model.

A bit more technically, the group created silicon dioxide nanotube anodes for lithium batteries, and in doing so, discovered they had significantly more energy capacity than with to the carbon-based anodes in use now.  Silicon polymer and battery used for the research.

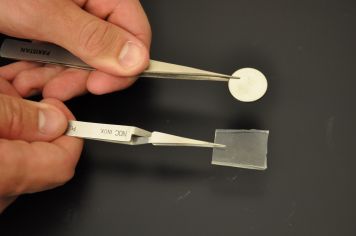

Silicon polymer and battery used for the research.

The discovery could have a major impact on several industries, in particular the electronics and electrical vehicle industries, both of which are constantly trying to get longer discharges out of batteries.

“We are taking the same material used in kids’ toys and medical devices and even fast food and using it to create next-generation battery materials,” said Zachary Favors, the lead author of the recently published, “Stable Cycling of SiO2 Nanotubes as High-Performance Anodes for Lithium-Ion Batteries.” The paper can be read online in the journal Nature Scientific Reports .

When the team first started out, they focused on silicon dioxide for three reasons: it's readily available, it’s environmentally friendly, and it’s proven useful, as it’s already in use with so many other products.

Those familiar with the history of silicon dioxide will likely point out that it’s already been used as an anode material in lithium ion batteries. The problem that existed in the past, though, was in being able to synthesize the material into highly uniform exotic nanostructures with high energy density and long cycle life.

The group came to discover silicon dioxide nanotubes were actually very stable in batteries: They were able to cycle their model 100 times without any loss in energy storage capability, and the researchers believe it could be cycled a few hundred times more before a decrease ever occurred.

Regarding next steps, the team will now focus on developing methods for scaling up production of the silicon dioxide nanotubes, in hopes that it could one day become a commercially viable product.

Story via ucr.edu

Advertisement

Learn more about Electronic Products Magazine