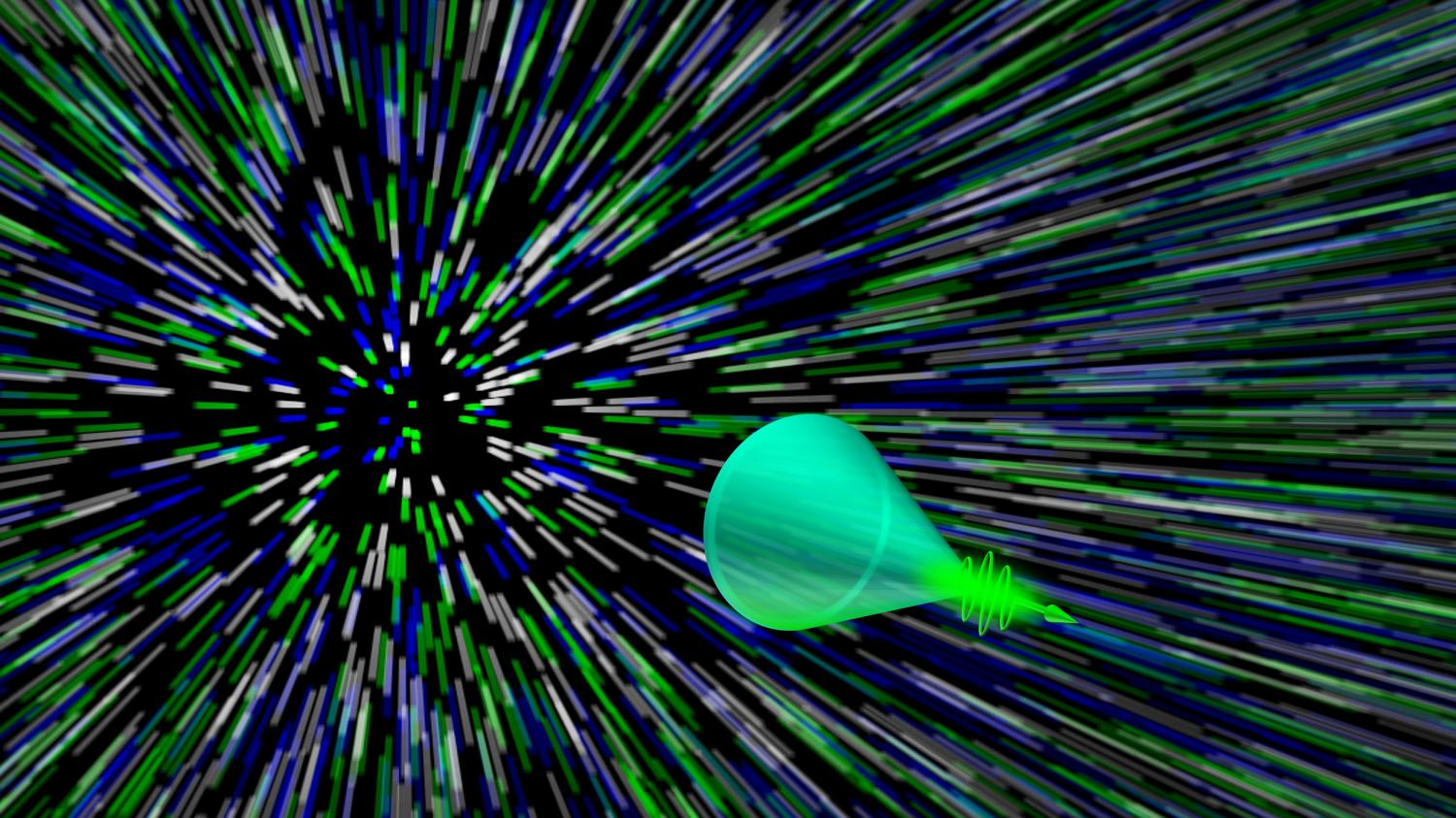

Researchers at Washington University in St. Louis are finally able to capture moving imagery of an optical Mach cone, thanks to a newly constructed apparatus. While scientists believed that the Mach cone existed, they were unable to capture photographic evidence of it in action — until now.

When an object moves faster than the speed of sound, it creates an acoustic cone that is experienced as a sonic boom. Though a variety of tools have been used to model light propagation across scattering media, instruments used in experimentation still lacked the ability to record this light scattering in real time. The new image-capturing system is able to successfully capture the Mach cone, as well as other events happening at breakneck speed. In a paper published in Science Advances , the team of researchers involved with the project explained their approach.

It was crucial that they look at the problem in a multifaceted way — how could they capture images happening at high speeds as well as slow down light? The answer to the second part of the question came easily — they simply shined a laser through something. For this experiment, dry ice particles in a tunnel were placed between aluminum oxide powder and silicone rubber plates. This allowed the light from the laser to travel more quickly in the tunnel and more slowly through the plates, causing an optical Mach cone to appear.

The first part of the problem presented a bigger challenge. In an effort to obtain imagery of the cone, researchers installed a variety of cameras next to the apparatus generating the cone. Among the three CCD cameras were a streak camera fitted with patterned filters that granted the ability to capture still 2D sequences of images, each assigned a code. Once the cone was created and then imaged, the 2D pieces were combined to create a 3D image, similar to the use of a CT scanner. In their abstract, the researchers explain, “The light-scattering event was imaged in a single camera exposure by lossless-encoding compressed ultrafast photography at 100 billion frames per second.” The remaining two cameras provided additional perspective and improved the overall resolution. The cameras are capable of capturing images at speeds approaching 100 billion fps.

The slowdown in light, combined with the three-camera approach, resulted in the first video image of the optical Mach cone. But Washington University’s team of researchers isn’t done — they believe that the same technique could be used to capture a number of other events, including the firing of individual neurons and other biomedical events.

Source: Phys.org

Advertisement

Learn more about Electronic Products Magazine