The ability to accurately recreate the human heartbeat outside of the body is a difficult task that may seem surprising to those unfamiliar with biotech. Now, a new class of the “lab on chip” category of microfluid devices — that is, those used to perform the complex laboratory tests needed to study pharmaceuticals — is being developed that successfully mimics the heartbeat using the a fundamental force of physics: Gravity.

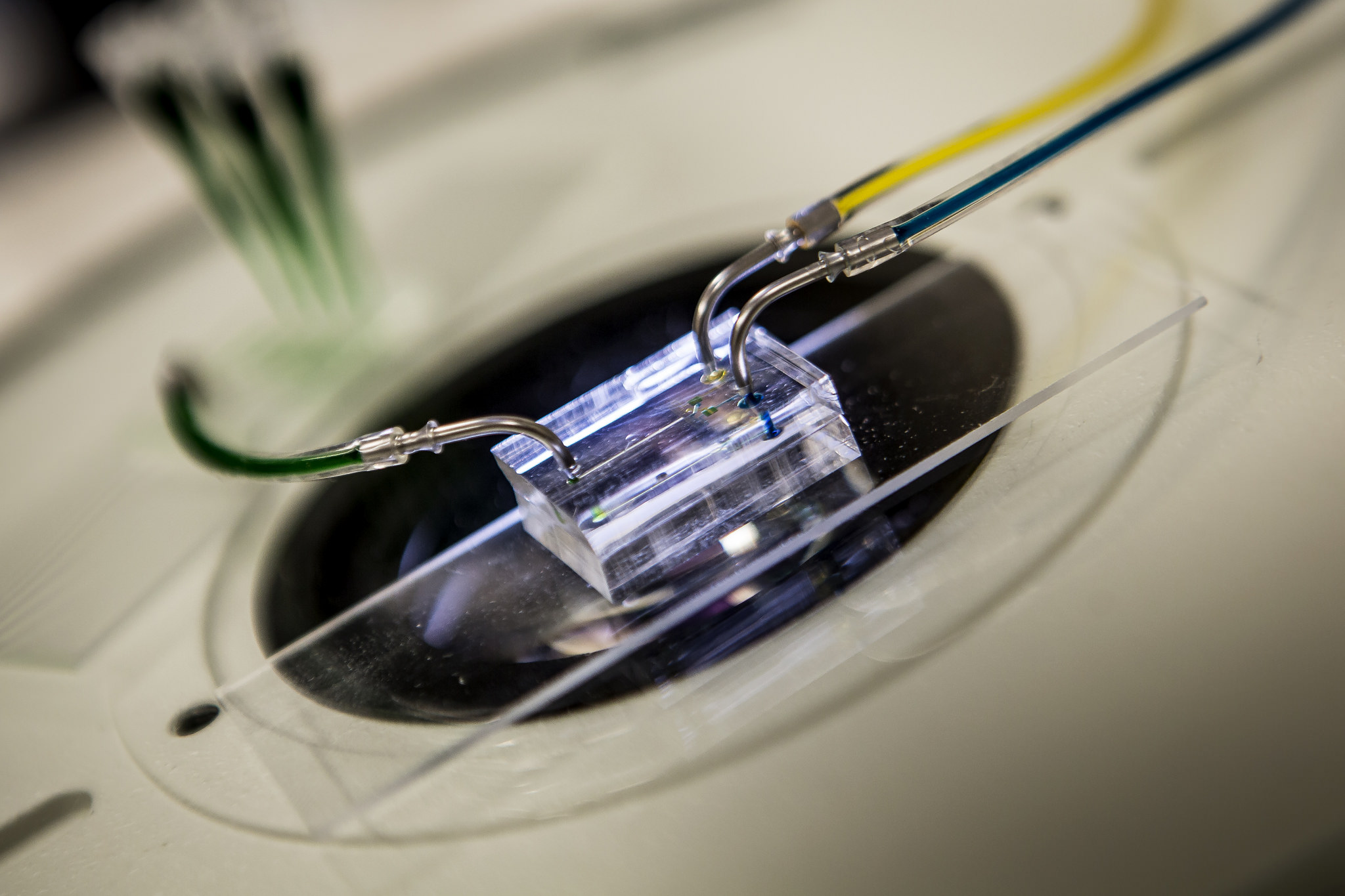

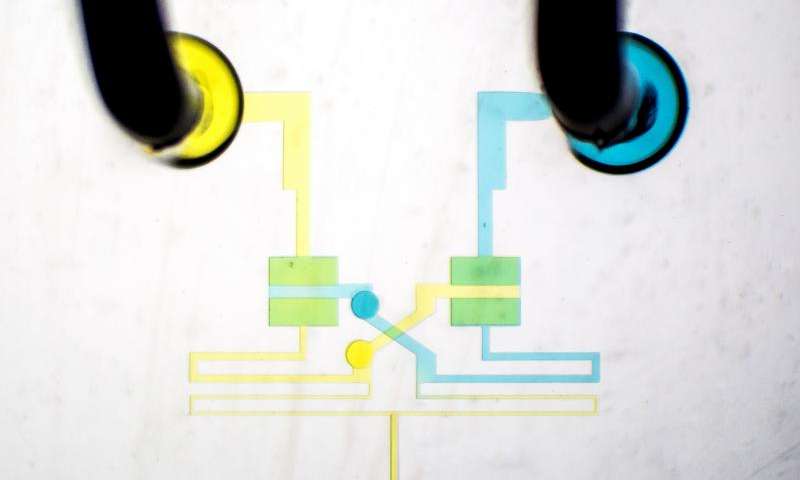

Crafted by the Biointerfaces Institute and Michigan Center for Investigative Research in Critical Care, the apparatus consolidates complex procedures into a small space by relying on microscopic, gravity-driven channels, capacitors, and switches to make liquids flow through it in a way that permits scientists to recreate a large variety of pulses and flow rates. This approach simplifies the otherwise complex procedure of testing new drug therapies by drastically cutting down on the required time and effort to test the human cells injected into it.

“The device gives us a bridge between the petri dish and the patient,” explains Shuichi Takayama, U-M professor of biomedical engineering and macromolecular science and engineering, one of the researchers behind the device.

The device’s efficiency arises from its ability to produce steady input pressure and simultaneously recreate the pulse rates and pressure of a wide variety of scenarios.

“Different types of patients have different pulse rates,” says Takayama. “For example, a septic patient's heart may beat faster or one blood vessel may have a different flow rate than another. Those factors influence how a given therapy will affect a cell. We can now replicate those factors and many others on a single chip and run the tests simultaneously.”

On the contrary, existing deices require a syringe pump to be steadily operated by a lab technician. Not only can the new device run multiple tests at once, but it can run unattended for long periods of time and cut down on the manpower needed per individual test.

In a sense, the chip operates much like the central processor within a computer that uses fluid instead of electricity. Sung-Jin Kim, assistant professor of mechanical engineering at KonKuk University and a former researcher on Takayama’s team, states that developing switches and capacitors able to use the fluid was the easy part, but successfully putting this into practice was the challenge.

“One of our biggest challenges was building a gravity-driven microfluidic circuit that works reliably,” he said. “Because unlike electronics, microfluidic switches need negative pressure to close properly. We eventually realized that we could control the pressure of the system by positioning the outflow well at a measured distance below the chip, creating just the right amount of pressure.”

Once the project is complete, the device’s initial uses will likely see the testing of new cardiovascular drugs and blood thinners; although Takayama suggests that the chip may easily be used to duplicate other biorhythms within the body such the brain or hormone delivery system.

“For example, we generally study liver cells' response to insulin by giving them a big dose all at once,” he said. “But in the body, the liver gets insulin from the pancreas in a series of tiny pulses. We could use this chip to duplicate those pulses and create a much more accurate model of what's happening in the body.”

Source: Phys.org

Advertisement

Learn more about Electronic Products Magazine