In an attempt to develop a more efficient and effective means of cleaning human blood of infection, a team of researchers led by Donal Ingber, a bionengineer at Harvard’s Wyss Institute for Biologically Inspired Engineering, has developed an artificial “biospleen” to filter blood.

This high-tech solution draws its inspiration from the human spleen and in experiments so far has proven capable of cleaning blood of everything from Escherichia coli (E. coli) to Ebola.

The group’s work was published in the September 14 edition of Nature Medicine .

Typically speaking, blood infections are difficult to treat, and sometimes lead to sepsis, an often-fatal immune response. Half the time, physicians are unable to diagnose the cause of an infection that leads to sepsis, and so resort to antibiotics that attack a broad range of bacteria.

It’s not always effective, and in some cases, can lead to an antibiotic resistance in the bacteria.

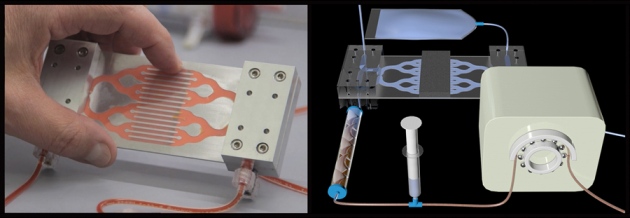

To overcome the many hurdles associated with blood-based infections, Ingber and his team developed a device that uses a modified version of mannose-binding lectin (MBL) — a protein found in humans that binds to sugars on the surfaces of 90+ bacteria, viruses, and fungi, as well as the toxins released by dead bacteria that trigger the immune overreaction in sepsis. The team coated magnetic nanobeads with MBL so that as the blood enters the biospleen, it passes the MBL-equipped nanobeads, which bind to the pathogens. A magnet on the biospleen then pulls the beads and their bacteria out of the blood, which can then be routed back into the patient.

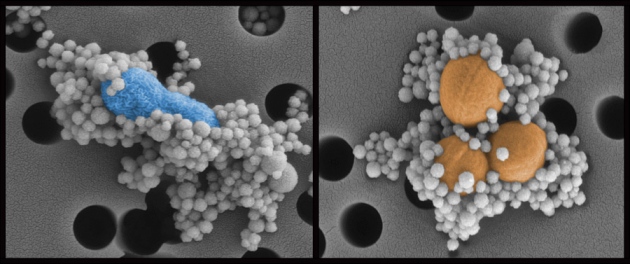

Magnetic nanobeads in the 'biospleen' device bind to Escherichia coli (left) and Staphylococcus aureus (right) and remove them from blood.

In terms of experimentation, Ingber’s team infected rats with either E. coli or Staphylococcus aureus and filtered the blood of some of the animals through the biospleen. Five hours post infection, 89% of the rats whose blood was filtered were still alive, as opposed to 14% of those that were infected but not treated. What’s more, the researchers found that the biospleen successfully removed more than 90% of the bacteria from the rats’ blood, and that the rats who were treated also had less inflammation in their organs, suggesting they would be less prone to sepsis.

The group also wanted to see whether the biospleen could handle the volume of blood in an adult human (roughly 5 liters), and so ran human blood mixed with bacteria and fungi through the biospleen at a rate of 1 liter per hour. They found the device was able to remove most of the pathogens within five hours.

Such a high degree of efficacy suggests the biospleen is already at the point where it can be used to, at the very least, control an infection. Once the biospleen has removed most pathogens from the blood, antibiotics and the immune system can fight off any remaining traces of infection, including those that lodge themselves in organs.

Ingber suggests the biospleen could also help treat viral diseases like HIV and Ebola, where the human body’s chances of survival are largely dependent upon lowering the amounts of virus in the blood to a negligible level. To this regard, the group is currently testing the biospleen on pigs.

Via Nature

Advertisement

Learn more about Electronic Products Magazine