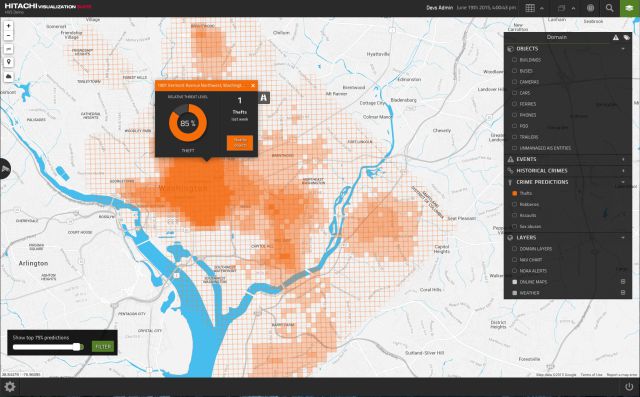

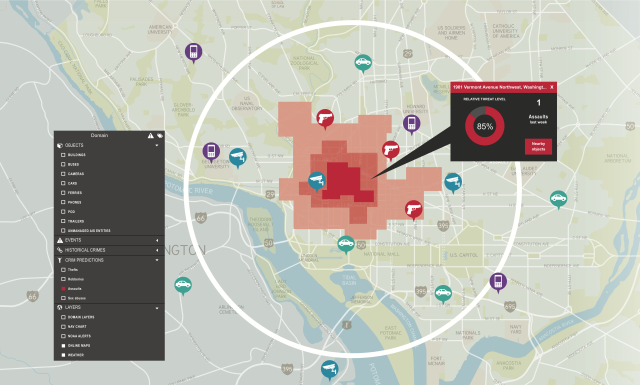

Japanese technology firm Hitachi may not have pre-cogs on staff, but it does have a machine learning software that it believes can specify when and where future crimes will occur down to a 200-square-meter-spot.

Called the Visualization Predictive Crime Analytics (PCA), the system predicts crime by simultaneously interpreting torrents of data — historical crime statistics, published transit maps, weather reports, and social media chatter to name but a few — before running it through the statistical software known as “R” to analyze everything and spew out patterns humans would otherwise miss.

“A human just can't handle when you get to the tens or hundreds of variables that could impact crime,” explains Darrin Lipscomb, an executive in Hitachi’s Public Safety and Visualization division, “like weather, social media, proximity to schools, Metro [subway] stations, gunshot sensors, 911 calls.”

The model is a enormous departure from traditional crime-predicting models that relay on the collective experience and judgment of the police officers to make assumptions about the relative threat level of each situation; PCA, by contrast, automatically deduces the relation of hundreds of variable, noting correlations and anomalies without human bias.

Such a monumental task is a product of machine learning, a new buzz word representing the massive-scale data processing that's recently become possible as a result of the huge distributed computing networks capable of rapidly processing data and storing big data in the cloud — systems like Amazon Web Services (AWS), Microsoft Azure, and Hitachi's own HDS cloud system.

Using this approach has allowed Hitachi to tap into social media as a means of understanding trends in human behavior, an aspect which improves prediction accuracy by as much as 15%. The technique applies the Latent Dirichlet allocation (LDA), a model of computational linguistics (the interactions between computers and human language), to sort through all geo-tagged posts and determine what significant events are occurring. To clarify, Lipscomb explains: “gangs, for instance, use these different keywords to maybe meet up or perform some action. I don't know what that keyword is…but with our approach we can actually pick out something that's abnormal, like someone's using an off-topic word, and using it in a very tight density or proximity, and that's going to get a bigger weight.”

Hitachi plans to test a proof of concept of PCA this October in handful of undisclosed US cities from the dozens whose police departments already benefit from the its sensor and surveillance program suite.

Whether the Minority Report reference in the opening sentence was caught or not, PCA raises some serious concerns. First, how do we ensure that PCA doesn't profile innocent people as criminals? Second, is the system even accurate? Addressing the first issue, Hitachi argues that PCA does not pinpoint suspects, but rather arms police officers with the additional resources needed to make better decisions. If anything, it should reduce police profiling.

“We're trying to provide tools for public safety so that [law enforcement is] armed with more information on who's more likely to commit a crime,” says Lipscomb. “I don't have to implement stop-and-frisk. I can use data and intelligence and software to really augment what police are doing.

Next, trials will be double-blind, meaning the software will run in the background while police departments continue functioning as usual for the duration of the test. Once testing is complete, both forms of data will be compared and made public, so that users can decide for themselves.

Source: Fast Company

Advertisement

Learn more about Electronic Products Magazine