While headlines and articles might suggest virtual reality’s ultimate destination is to wind up as the next great form of modern-day entertainment, researchers have quietly begun exploring the technology’s health benefits—namely, as a means for treating mental illness.

The latest research, published in the British Journal of Psychiatry Open, has confirmed virtual therapy could help with depression.

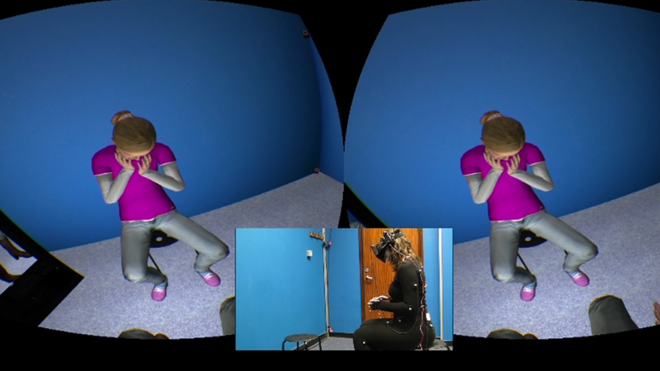

The project, part of a continuing study at the University College London, took 15 people — 10 women and 5 men between 23 and 61 years of age — and outfitted them with virtual reality headsets. When the program began, an adult version of the patient was projected into a virtual reality mirror. The patient was then asked to mentally identify with the adult avatar, which replicated the patient’s body movement in a process known as “embodiment.”

During this exercise, the patients were prompted to notice a separate avatar of a small crying child. They were then instructed to say compassionate phrases to the child to try and comfort it — things like asking the child to remember a time when it was happy, think of someone who love them, and so on.

At this stage of the experiment, the roles were then reversed, wherein the headset altered the patient’s point of view to be that of the child, whereupon it took on the patient’s body movements. The patient then heard the same phrases of compassion spoken back to them from the adult avatar, in the patient’s own voice.

Professor Chris Brewin, the study’s lead author, said the results were promising, and that the patients described the experience as being “very powerful”. Statistically, of the 15 patients, nine recorded reduced levels of depression one month after the trial. Of this sub-group, four reported a “clinically significant drop in depression severity.”

The rest recorded no changes.

These sessions lasted for 45 minutes; each patient received three sessions total. Professor Brewin said he believes the effects of the treatment could last for up to a month.

“People who struggle with anxiety and depression can be excessively self-critical when things go wrong in their lives,” Brewin explained. “In this study, by comforting the child and then hearing their own words back, patients are indirectly giving themselves compassion. The aim was to teach patients to be more compassionate towards themselves and less self-critical.”

“We now hope to develop the technique further to conduct a larger controlled trial, so that we can confidently determine any clinical benefit,” added co-author Professor Mel Slater.

To learn more, download the paper, entitled: Embodying self-compassion within virtual reality and its effects on patients with depression.

Via the BBC

Advertisement

Learn more about Electronic Products Magazine