As technology launches us into a new age with many incredible high-tech developments, it may also give rise to a new Industrial Revolution. Called “Industry 4.0”, it is a new method of production that may hold the key to creating the fourth Industrial Revolution since the dawn of the modern world.

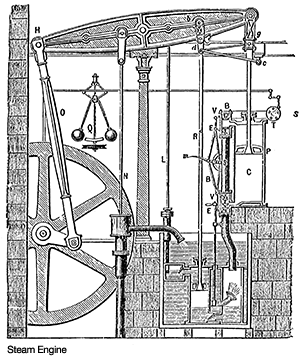

About 250 years ago, James Watt’s improvements to the Newcomen steam engine in the late 18th century kick started the First Industrial Revolution . Watt did not invent the steam engine, but his numerous innovations increased the productivity of the textile industry by three orders of magnitude, bringing about the age of mechanized factories.

The Second Industrial Revolution dates from Henry Ford’s introduction of the assembly line in 1913, which resulted in a huge increase in production of Model T’s – over 15 million by the time they were discontinued in 1927. Soon every other manufacturing industry was using assembly lines to increase efficiency and productivity as well as cut costs, launching the era of mass production.

The Third Industrial Revolution resulted from the introduction of the computer onto the factory floor in the 1970s, giving rise to the automated assembly line. For mechanical work, computers increasingly replaced humans, another major upturn in productivity. Today, seemingly every manufacturing function that can be automated has been. Highly automated factories turn out the complex consumer electronics products that we take for granted at prices we can afford.

Industry 4.0

In the vision of Industry 4.0, “cyber-physical production systems” will use sensor-laden “smart products” that will tell machines how they should be processed. The processes will govern themselves in a decentralized, modular system. Smart embedded devices will start working together wirelessly, either directly or via either the Internet ‘cloud’, or the Internet of Things (IoT), to once again revolutionize production. Rigid, centralized factory control systems will give way to decentralized intelligence as machine-to-machine (M2M) communication hits the shop floor. This is the Industry 4.0 vision for the Fourth Industrial Revolution .

The concept of cyber-physical systems (CPS) was first expressed by Dr. James Truchard, CEO of National Instruments, in 2006, based on a virtual representation of a manufacturing process in software. In January 2012, the German Federal Ministry of Education and Research set up a working group to draft comprehensive strategic recommendations for implementing “Industry 4.0”, a term coined by the group. The Industry 4.0 Project is now part of the German government’s official High-Tech Strategy, which it is actively pursuing together with private sector partners. Discussions about Industry 4.0 took center stage at April’s Hannover Fair, which is why we are suddenly hearing about it.

Industry 4.0 is currently more of a vision than a reality, but it is one with potentially far reaching consequences. The concept continues to evolve as people think of innovative ways to implement it, but some things are already clear:

• Sensors will be involved at every stage of the manufacturing process, providing the raw data as well as the feedback that is required by control systems.

• Industrial control systems will become far more complex and widely distributed, enabling flexible, fine-grained process control.

• RF technologies will tie together the distributed control modules in wireless mesh networks, enabling systems to be reconfigured on the fly in a way that is not possible with hard-wired, centralized control systems.

• Programmable logic will become increasingly important since it will be impossible to anticipate all the environmental changes to which control systems will need to dynamically respond.

• Smart, connected embedded devices will be everywhere, and designing and programming them will become that much more challenging – not to mention interesting and rewarding.

Most of the techniques and technologies needed to implement Industry 4.0 exist today. For example, the radios, sensors, and GPS modules used for asset tracking could just as easily track circuit board assets around the factory floor as they evolve from slabs of FR4 into server blades. The Industry 4.0 spin is that instead of simply attaching an RFID tag and passively tracking the PCB down a linear assembly line, the pick-and-place module could alert inventory when it was running short of memory chips. If the response was that they could not be restocked in time, then all the relevant machines in the entire factory – from the cutting machines and drill presses right through to the systems assembly robots – would reprogram themselves to begin producing the next product for which all parts were in stock, drawing them down from remote inventory as needed, automatically delivered to the right machine just-in-time. Meanwhile second-source suppliers would be alerted and their assets would be automatically reconfigured accordingly. This would result in an enormous savings in time and cost compared to what current heavily automated factories can deliver today.

Revolution or Evolution?

Earlier Industrial Revolutions did not happen overnight, and were not recognized as such at the time. Industry 4.0 may or may not be recognized as revolutionary – rather than evolutionary – in retrospect. But it is a natural consequence of M2M communication further automating the factory floor, and like its predecessors, it should result in more plentiful, lower cost products—a net benefit for all concerned. Whether revolution or evolution, industrial production is about to become a lot more efficient!

John Donovan is editor/publisher of www.low-powerdesign.com and ex-Editor-in-Chief of Portable Design, Managing Editor of EDN Asia, and Asian editor of Circuits Assembly and Printed Circuit Fabrication. He has 30 years experience as a technical writer, editor and semiconductor PR flack, having survived earlier careers as a C programmer and microwave technician. John has published two books, dozens of manuals and hundreds of articles. He is a member the Association for Computing Machinery (ACM) and a Senior Member of the IEEE. His favorite pastimes include ham radio, playing with his kids and scouting Texas for the best BBQ joints.

John Donovan is editor/publisher of www.low-powerdesign.com and ex-Editor-in-Chief of Portable Design, Managing Editor of EDN Asia, and Asian editor of Circuits Assembly and Printed Circuit Fabrication. He has 30 years experience as a technical writer, editor and semiconductor PR flack, having survived earlier careers as a C programmer and microwave technician. John has published two books, dozens of manuals and hundreds of articles. He is a member the Association for Computing Machinery (ACM) and a Senior Member of the IEEE. His favorite pastimes include ham radio, playing with his kids and scouting Texas for the best BBQ joints.

Suzanna Brooks joined Mouser Electronics in 2011 as a Technical Content Specialist and writes web content about the newest embedded and optoelectronic products available. Suzanna holds a Bachelor of Science degree from Embry-Riddle Aeronautical University and is a private pilot.

Advertisement