By Richard Quinnell, editor-in-chief

Product development is in the midst of a profound shift as the advent of low-cost development hardware and open-source software along with crowdfunding meets rising opportunity in robotics, the Internet of Things, and smart consumer device markets. The hardware and software trends are democratizing device creation and the rising opportunities are providing incentives for non-traditional developers to try out their ideas and bring them to market while crowdfunding is providing the means. The result is a new generation of developers sometimes interchangeably called makers, designers, and engineers, but there is a difference among them, and it can be critical to a product’s success.

A maker, as the name implies, is someone who makes things — usually something novel. This rather broad term encompasses product developers as well as artists, craftspeople, and others who produce a tangible object. There are no other restrictions. Age, education level, materials used, and the like are all open-ended. A maker makes, period.

By this definition alone, it is easy to see how makers, designers, and engineers can all be lumped together in people’s minds. For the most part, they are all involved in making things. But there is a subtle difference in approach that merits consideration.

To my way of thinking, a maker works mostly by virtue of imagination and tinkering. They may or may not start out with a goal in mind, and their creative path is mostly a matter of trying things out, refining their initial concept as they go. It is an exploratory approach rather than a pre-planned one and can lead to many failures as well as to some surprising innovations.

Designers take a different approach. They plan out their creation, often to a high degree of detail, before starting to make it. This approach gives them a roadmap to follow toward a clearly defined goal. There may be changes made to the design as implementation progresses (in fact, it’s almost inevitable), but by and large, their implementation efforts follow the pre-defined plan. The end result is usually more refined, more robust, and better-suited to its purpose than something that is simply “made.” And often, the whole process yields its final results faster than the maker approach despite the seemingly “unproductive” time spent in planning.

To use this approach effectively, though, the designer must understand the implementation process well enough to anticipate most obstacles and determine how to handle them ahead of time. This requirement represents one of the essential differences between a designer and a maker — designers must know enough about what to do, how to do it, and what the results are likely to be that they are able to chart their entire course before setting off.

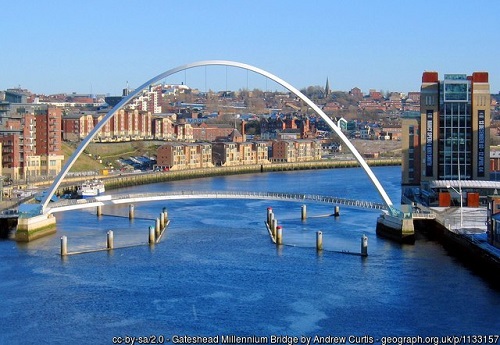

The Gateshead Millenium Bridge is a curved pedestrian river crossing that can be rotated up to provide clearance for boat traffic.

Engineers are also designers, but with one added wrinkle: analysis. Like a designer, an engineer will plan out their creation before beginning implementation. But engineers also plan beyond the implementation to consider mass production and maintenance needs, stress, environmental effects and wear-and-tear, cost to produce and to maintain, and a host of other factors that may not affect form or function but do affect practicality. Evaluating the design against these factors takes both technical knowledge and mathematical analysis.

Design and engineering often go hand in hand. Creating the elegant Gateshead Millenium Bridge, which tilts up to form a double arch to let boats through, involved both the creative design process to define the bridge’s shape and operation as well as the analytic engineering needed to ensure that the structure could move as intended as well as operate reliably for decades.

It’s also worth noting that those called makers may have designed or even engineered their creations before beginning fabrication. It’s important to realize that the primary task of those called designers and engineers is development and articulation of the plan; they may not actually be the makers. And although engineers often do their own designing, they may also simply focus on analyzing (and adapting) someone else’s design. Similarly, designers may not always do engineering, creating the plan but not doing the detailed analysis.

So it’s easy to see how the three can become conflated, yet the differences among them are important. Nearly everyone with a basic understanding can be a maker and produce a single instance of their idea. It takes deeper knowledge to be a designer, creating a plan for someone (and not necessarily the designer) to follow that reliably yields the intended product. Engineering is an analytic discipline that requires both substantial training and experience and is essential to ensuring that a design plan will yield a product that is durable, reliable, safe, manufacturable, and cost-effective.

Advertisement

Learn more about Electronic Products Magazine