By Richard Quinnell, editor-in-chief

There are many microcontrollers and associated modules vying to become the basis of Internet of Things (IoT) designs, but many industrial applications need the performance that only a full-fledged microprocessor can provide. Such processors need operating systems to run their feature-rich applications code. Now Microchip is making the design of such powerful IoT systems easier with a new system-on-module (SoM) that clears the path for bringing mainline Linux to the IoT.

From the designer’s point of view, there are considerable differences between using a microcontroller (MCU) and a microprocessor (MPU) as a product’s foundation. Because microcontrollers lack integral system and program memory as well as peripherals, for instance, these vital resources must appear on the PCB as separate components. Their presence, in turn, greatly complicates development as designers are forced to deal with signal integrity and routing issues for high-speed connections to things like DDR memory and gigabit Ethernet physical layers (PHY). For industrial applications, in which long product life is essential, using peripheral and memory devices that must be drawn from an ever-evolving consumer market complicates component sourcing as well.

Software development can be equally challenging. MPU-based designs typically require the use of an operating system (OS) to facilitate the creation and maintenance of application code. But finding developers experienced with proprietary code can be challenging. Having the ability to use an industrialized version of the ubiquitous Linux would be an advantage.

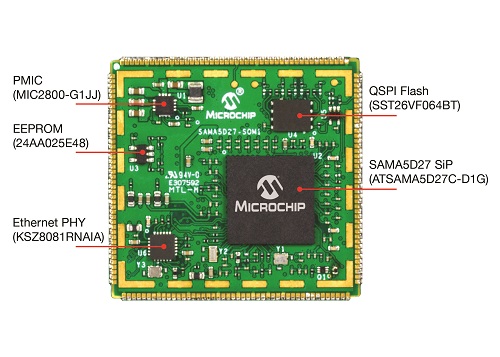

With its introduction of the ATSAMA5D27 SoM, Microchip is addressing all of these issues. The SoM is based on the SAMA5D2 system-in-package (SiP), which integrates a Cortex-A5 processor with up to 1 Gb of DDR2 memory to eliminate the need for manual impedance matching. The module combines the SiP with Flash memory, boot EEPROM, Ethernet PHY, and power management chips onto a PCB to further reduce the designer’s task. The module has soldering pads located on the edge, allowing developers to simply drop the SoM onto a four-layer PCB and have all of the difficult design issues resolved.

The SoM also resolves sourcing issues. Microchip fabricates most of the parts used and has long-term supply agreements for the remainder. Industrial developers need not worry about end-of-life issues on memory or other key chips during their design’s production life. This also helps insulate manufacturers from the major pricing fluctuations that characterize the DRAM market.

For software, the SoM supports mainline Linux so that development teams can draw from an extensive talent pool. Furthermore, this version of Linux is intended for long-life applications and will be actively maintained for up to six years.

With onboard interfaces for LCD displays, a Bayer camera, capacitive touch, and an audio subsystem, Microchip’s SoM, in many ways, exhibits characteristics similar to those of experimental and hobbyist-oriented modules. But there are critical differences. The Microchip modules will be available worldwide and in full-production volumes to support commercial usage and can be customized to meet unique needs. Furthermore, they meet payment card industry (PCI) security standards with features such as secure boot, memory integrity checker, and on-the-fly encrypted communications between the MCU and system memory.

The SoM is available now for $39 in 100-unit quantities, and the SiP on which the module is based is available starting at $8.62 each in 10,000-unit quantities. There is also a development board available for $249.

Advertisement

Learn more about Electronic Products MagazineMicrochip Technology