By Brian Santo, contributing writer

NASA is heading for a whole new level of harsh. Icarus got close enough for the sun to melt the wax in his wings. NASA’s Parker Solar Probe—set to launch in July 2018—is going to get far closer to the Sun than any previous probe – close enough for the sun to melt stainless steel, titanium, and silicon.

There have been 19 orbital missions to the sun thus far by one count, all with US participation. Parker is one of at least four planned in the next few years, including one proposed by Russia and another by India.

The primary goals for the Parker mission are to trace how energy and heat move through the sun’s corona (it’s upper atmosphere) and to explore what accelerates the solar wind as well as solar energetic particles. The probe will carry four instrument suites designed to study magnetic fields, plasma and energetic particles, and image the solar wind.

Learning more about the solar wind is not an academic exercise. Space weather (of which solar wind is a major component) can change the orbits of satellites, shorten their lifetimes, and interfere with onboard electronics, NASA reminds. Solar emissions are proven to disrupt communications systems. The space agency quotes the National Academy of Sciences which reports that without advance warning, a huge solar event could cause $2 trillion dollars in damage in the US alone, and leave the eastern seaboard of the US without power for a year.

Meanwhile, private interests are agitating for missions to Mars, capturing popular interest. Some of the most intense skepticism about those projects is rooted in the lack of understanding of space weather. Mars mission crews would be subject to significantly more space weather than even the most experienced astronauts on the International Space Station have ever endured. The more we learn about space weather, the better prepared any potential manned missions beyond the Earth will be.

Collecting the required data on solar emissions requires entering the corona, however, previously impossible in part because the temperature there is roughly 2,500 degrees Fahrenheit – and that’s before taking into account a level of radiation no probe has previously experienced.

The probe might be subjected to temperatures up to 2,500 degrees, but parts of the solar atmosphere can get significantly hotter; flares can reach 18 million degrees. The sun’s surface meanwhile, is only 10,340 degrees F, according to NASA. While there are theories about how the solar atmosphere can get so very much hotter than the solar surface, Parker is expected to provide some proof.

To protect the Parker probe and its instrument pack against the heat, it will be enveloped by a 4.5-inch-thick (11.43 cm) carbon-composite shield, NASA said. The shield should keep the probe’s internals at roughly room temperature, NASA told Space .com.

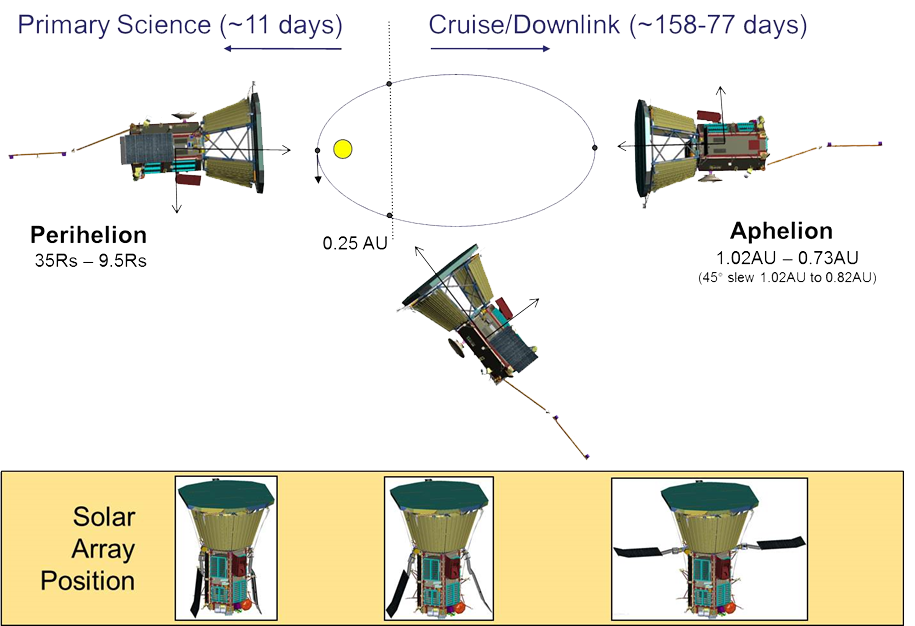

The probe is set to launch from the Kennedy Space Center as early as July 31. It will head toward Venus so it can use that planet’s gravity to sling it toward the sun. Parker is scheduled for 24 flybys of the sun, using a total of seven gravity boosts from Venus to keep it going on its planned path.

Over the course of 7 years, Parker’s orbits will get gradually closer to the sun. According to NASA, the spacecraft will fly through the sun’s atmosphere as close as 3.9 million miles to the sun’s surface, well within the orbit of Mercury and more than seven times closer than any spacecraft has come before.

The Parker probe is the first NASA project to be named after someone who’s still alive. The honoree is Eugene Parker, an astrophysicist now at the University of Chicago, who in 1958 was the first to predict the existence of what is now commonly known as solar wind.

Source: NASA

Advertisement

Learn more about Electronic Products Magazine