By Richard Quinnell, EiC, Electronic Products

Voice activation is the hot trend in electronic products these days, but there are many situations in which voice isn’t practical. Noisy environments, eavesdropping concerns, and individuals who, for one reason or another, simply cannot speak could all benefit from a hands-free alternative to voice-based control. Now researchers at Toyohashi University of Technology in Japan may have found an answer: they’re teaching computers how to read minds.

This isn’t some form of machine telepathy, though, wherein the computer can pry into all of your thoughts and darkest secrets. It’s a method for teaching computers to recognize when the subject is speaking specific words, using brainwaves alone. Sound isn’t involved, only the subject’s deliberate attempt to voice a word. So, in effect, the computer is reading their minds about what they are trying to say. But only in a limited way.

According to the University’s press release on the subject, the researchers have developed a technology that allows the computer to recognize with 90% accuracy when subjects are speaking the numbers zero through nine, and with 60% accuracy nearly 20 other monosyllables (in Japanese), using brainwave readings alone. The details of their technology will be presented in a paper at the upcoming Interspeech 2017 conference in Stockholm, but the press release hints that they are using a totally new approach to brainwave recognition.

Brainwaves can be monitored using an electroencephalogram (EEG), but correlating those readings with specific thoughts has been far beyond conventional computer analysis techniques. Even when the effort is restricted to speech decoding, a vastly simpler task than interpreting unfettered thoughts, conventional processing fails. AI techniques such as deep learning fall down, in part, because of the difficulty in collecting enough of data for the machine to find the underlying general patterns.

The Toyohashi approach, according to the release, is based on holistic pattern recognition using category theory, also called composite mapping. This is an advanced mathematical technique stemming from algebraic topology, and is used to study the mapping of one set of things to another. In this case, it seems, the technique is being used to learn how brainwave activity maps to specific words, and it requires far fewer training examples to achieve high accuracy than other machine-learning techniques.

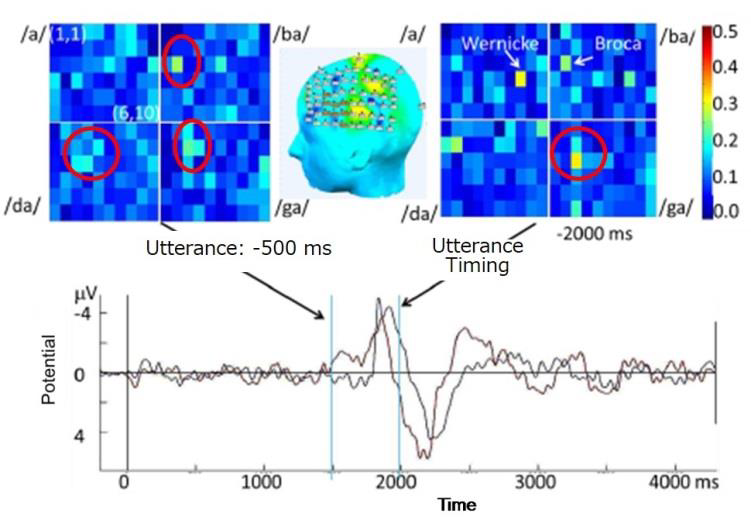

The press release doesn’t go into any further detail — we’ll have to wait for the paper to be presented to get that information — but it does provide some intriguing clues in the form of images apparently taken from the paper. As seen below, the technique seems to involve the AI learning how to recognize the relationships between spoken words and the timing, duration, intensity, and location of brainwave signals that the EEG is picking up.

The region of brain activated when speaking varies with the syllable, as does intensity and timing. (Source: Toyohashi University of Technology)

The limited number of monosyllables that the system is currently able to recognize even at 60% accuracy may seem disappointing (or comforting, depending on one’s level of AI paranoia), but it represents a substantial step forward in converting brainwave activity into actionable information. As the release points out, humans themselves are able to understand whole sentences with only an 80% recognition rate of the individual monosyllables, so expanding the technique to achieve full speech recognition may not be as far of a reach as it seems.

Full brainwave-based speech recognition is certainly a goal of the research team. The University states that lead researcher Emeritus Professor, Tsuneo Nitta, and his team hope to eventually create a brain-computer interface (BCI) that recognizes utterances without voicing. This would allow, among other things, “speech” control of systems simply by silently thinking the words. Coupled with voice synthesis, this could also return the power of speech to the mute and other vocally impaired users, such as “locked-in” coma victims. The team’s ambition is to refine their system to use fewer electrodes and be able to connect to smartphones within five years.

Advertisement

Learn more about Electronic Products Magazine