Researchers from the University of Michigan have created a new device referred to as the “kidney-on-a-chip”. Its purpose is to allow doctors to measure the effect of medicine on kidney cells prior to administering it to the patient.

Should the technology prove scalable, it is being suggested as an avenue to more accurate drug dosages — from the most basic of medicines to the oft-toxic chemicals included in those administered to patients in intensive care units.

“When you administer a drug, its concentration goes up quickly and it's gradually filtered out as it flows through the kidneys,” said Shuichi Takayama, University of Michigan professor of biomedical engineering. “A kidney on a chip enables us to simulate that filtering process, providing a much more accurate way to study how medications behave in the body.”

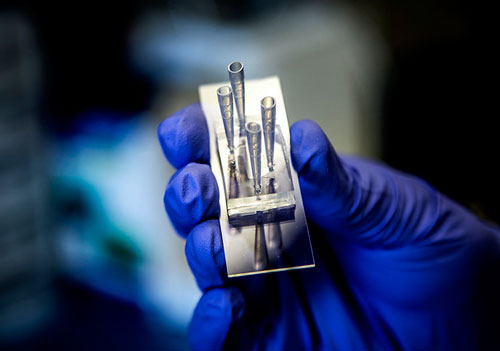

In short, the technique uses a microfluidic chip device to deliver a precise flow of medication across cultured kidney cells.

It’s believed to be the first time such a device has been used to specifically study how a medication behaves in the body over time, also referred to as it “pharmacokinetic profile.”

Takayama explained that the artificial device will allow doctors to run tests consecutively in a controlled environment, and alter the flow of the medication to simulate different levels of kidney function.

“Even the same dose of the same drug can have very different effects on the kidneys and other organs, depending on how it's administered,” said former U-M researcher Sejoong Kim, an associate professor at Korea's Seoul National University Bundang Hospital. “This device provides a uniform, inexpensive way to capture data that more accurately reflects actual human patients.”

The team conducted a study using the technology, during which two different dosing regimens were compared using gentamicin — an antibiotic commonly used in intensive care units. The microfluidic device used to administer the chemical featured a thin, permeable polyester membrane as well as a layer of cultured kidney cells between the top and bottom compartments.

The gentamicin solution was applied to the top compartment, and allowed to filter through the cells and membrane, thereby simulating the natural flow of medicine through a human kidney. The first test began with a high concentration, which quickly tapered off — this simulated a once-daily drug dose. The other test used a lower concentration, which stayed constant, to simulate a slow infusion of the drug.

Upon review, the team found that a once-daily dose of the medicine is less harmful than a continuous infusion, even though both tests delivered the same dose of chemical. They hope these results can be used to help doctors improve dosing regiments for gentamicin in the future.

More importantly, though, they were able to demonstrate that the technology could be used to study the flow of medication through a human organ.

“We were able to get results that better relate to human physiology, at least in terms of dosing effects, than what's currently possible to obtain from common animal tests,” Takayama said. “The goal for the future is to improve these devices to the point where we're able to see exactly how a medication affects the body from moment to moment, in real time.”

He and the team believe that the techniques used in the study can be scaled to a variety of other organs and medicines, thereby allowing doctors to collect important information on how these chemicals come to affect the heart, liver, kidneys, and other organs in the body.

Additionally, it could help drug makers improve drug dosing regiments; this, in turn, could bring new medications to market faster.

To learn more, check out the clip the University of Michigan team put together about the new kidney-on-a-chip technology:

Via the University of Michigan

Advertisement

Learn more about Electronic Products Magazine