Researchers from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology’s (MIT) Laser Biomedical Research Center in Cambridge, MA, have teamed up with the nearby Massachusetts General Hospital (MGH) in hopes of improving application of pain-blocking epidural injections, often given during childbirth. They have created a new sensor that they believe can be refined to fit in an epidural needle, thereby helping anesthesia doctors guide the needle to the correct location.

Currently, anesthesiologists must guide a four- to six-inch needle through multiple layers of tissue to reach the epidural space surrounding the spinal cord. They know when the needle has reached the right spot based on how the tissue’s resistance changes. “The needle is placed essentially blindly,” says T. Anthony Anderson, an anesthesiologist at MGH and an assistant professor at Harvard Medical School.

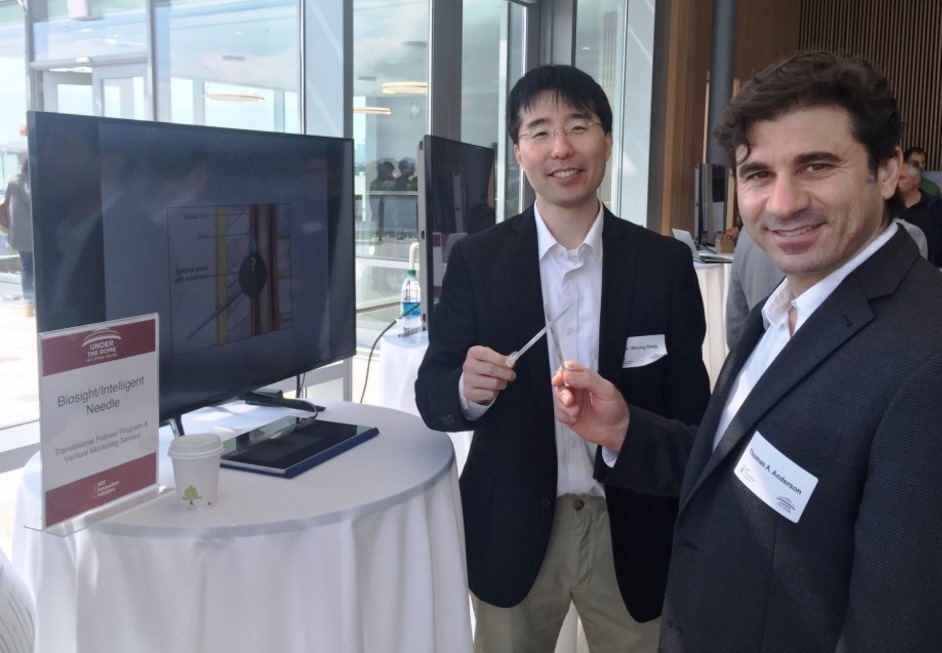

MIT research scientist Jeon Woong Kang (left) and Dr. T. Anthony Anderson show off prototype sensor-needle systems at a recent MIT open house.

Since some patients’ tissues vary from the usual pattern, it can be difficult to determine whether the needle is in the right place. This can lead to reduced effectiveness of the pain-killing drug or, in rare cases, a stroke or spinal cord injury.

Anderson teamed up with researchers at MIT, headed by Peter So, a professor of mechanical engineering and biological engineering. MIT research scientist Jeon Woong Kang designed an optical sensor that relies on Raman spectroscopy and could be placed at the tip of an epidural needle. The sensor uses light to measure energy shifts in molecular vibrations and thus provide detailed information about the chemical composition of tissue. By measuring concentrations of albumin, actin, collagen, triolein, and phosphatidylcholine, different tissue layers can be identified with 100% accuracy. “From the chemical composition, you can identify all tissue layers, from skin to spinal cord,” Kang says.

The researchers need to do further animal studies before testing it in human patients, and want to reduce the diameter of the sensor from 2 to 0.5 mm in keeping with the size of most epidural needles. The sensor may also be used in other procedures involving needles, such as cancer biopsies. Supported by MIT entrepreneurship programs, the researchers have started a company, Medisight Corp. (www.medisightcorp.com), to continue developing the technology.

Advertisement

Learn more about Massachusetts Institute of Tec