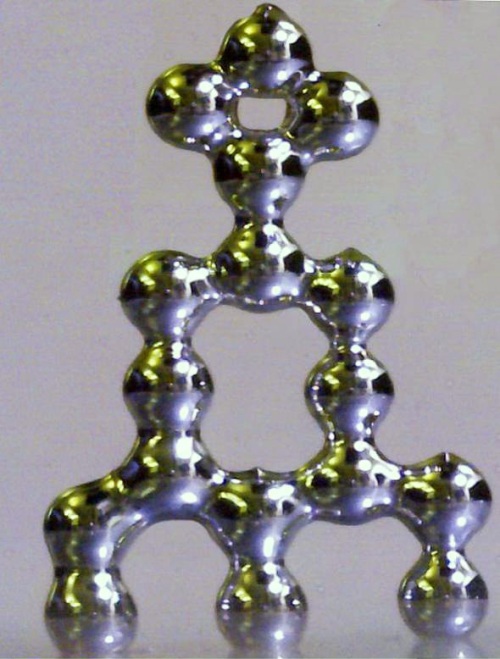

A group of researchers out of North Carolina State University used an alloy of two metals, gallium and indium, to 3D-print liquid metal structures.

NCSU researchers have developed three techniques for 3D printing liquid metal structures.

The two metals are liquid at room temperature but form a skin when exposed to the air. When they’re run through a 3D printer, the shapes they create can be stretched without reverting to blobs and dribbles.

“It’s difficult to create structures out of liquids, because liquids want to bead up. But we’ve found that a liquid metal alloy of gallium and indium reacts to the oxygen in the air at room temperature to form a ‘skin’ that allows the liquid metal structures to retain their shapes,” says Dr. Michael Dickey, an assistant professor of chemical and biomolecular engineering at NC State and co-author of a paper describing the work.

This discovery could be used for microcircuit design, wearable electronics, and might even be a major turning point in the development of stretchable electronics.

How it works

Three techniques were developed. In one, the 3D printer uses a syringe to stack droplets of the alloy on top of one another. The droplets themselves, as mentioned before, retain their shape when exposed to air. This allowed the researchers to shape the metal however they saw fit.

“The metal forms a very thin layer of oxide and because of it, you can actually shape it into interesting shapes that would not be possible with normal liquids like water,” said Dickey.

As for the second technique, liquid metal is injected into a polymer template, so that it takes on a specific shape. The template is next dissolved, leaving behind the bare, liquid metal in the desired shape.

The third technique was developed for the purpose of creating liquid metal wires, which retain their shape even when held perpendicular to the substrate.

All three can be viewed in the video below.

VIDEO

These techniques could potentially be used to make connections between electronic components that would not break if the device was pulled or twisted.

“The resulting structures are soft, and if you embed them in, say, rubber, for example, you can create structures that are deformable and stretchable,” Dickey explains.

Looking ahead

Flexible electronics are fast becoming a serious topic of discussion. Companies like Samsung, Nokia, and LG are all beginning to experiment with displays that can be bent and gadgets that are twistable.

What is holding them back is that these electronics were not stretchable. This hurdle may have been cleared with the discovery made by the NCSU team.

For now, though, Dickey and his team are exploring ways to further develop all three of the aforementioned printing techniques, along with how best to use them in electronics applications and with current 3D printing technologies.

Download the group’s full study, “3D Printing of Free Standing Liquid Metal Microstructures”, in the journal, Advanced Materials (free).

Story via: ncsu.edu

Advertisement

Learn more about Electronic Products Magazine