A group of British scientists will soon embark on a first of its kind mission to the South Pole — one that involves everything from robotic submarines to sensor-bearing seals — in an effort to better understand what’s causing the rapid loss of ice on the West Antarctic Ice Sheet.

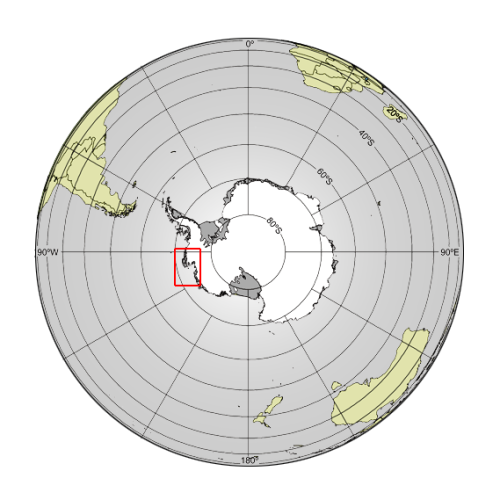

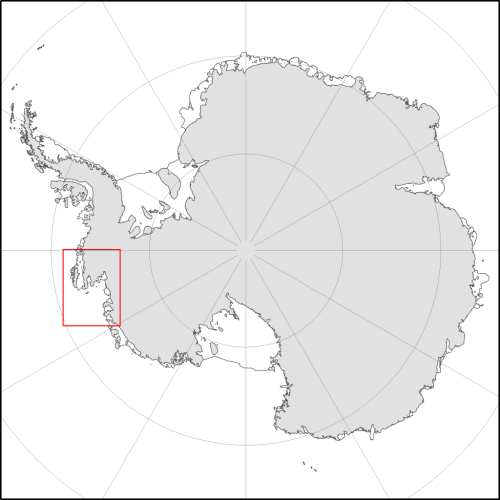

The team will be travelling to the Amundsen Sea region of Antarctica to study the area’s shrinking glaciers. A major part of the study will be the Pine Island Glacier, the longest and fastest-changing glacier on the ice sheet.

“We used to think that the volume of water flowing from Antarctica's melting glaciers and icebergs into the ocean was equal to the amount of water falling as snow onto the ice sheet, and that this process was keeping the whole system in balance,” said Andy Smith, a glaciologist with the British Antarctic Survey and science program manager for the Natural Environment Research Council's iSTAR program, which is leading the new Antarctica mission.

“But Pine Island and Thwaites glaciers on the West Antarctic Ice Sheet are losing ice at a faster rate than they are being replenished,” Smith continued. “This affects sea level all over the world. The speed of changes to this region has taken scientists by surprise, and we need to find out what's going on.”

Using modern-day technology to assess the effects of climate change

The team will travel to Antarctica in November and spend ten weeks traveling 600 miles across the West Antarctic Ice Sheet. During the trip, ground-based radar and seismic technologies will be used to map out the area below the Pine Island Glacier and assess the state of the bed in hopes of determining how subsurface conditions affect the flow, thickness, etc. of the ice. In regards to areas of the ice that are inaccessible, satellite remote sensing technology will be used.

Come January, a team of researchers will sail into the Amundsen Sea as part of a 30-day trip, during which the crew will install ocean-temperature-measuring instruments. The point behind doing this is to determine when, where, and how warm ocean water is when it’s near the ice.

The group will also deploy a team of ocean robots called “Seagliders,” as well as an unmanned submarine to measure ocean temperature, salinity, and the speed of currents at various depths. The group hopes that all of this data will help determine how ocean currents transport heat beneath the ice shelf, and how climate change is affecting this part of Antarctica.

Four autonomous radar instruments will also be used to monitor the gradual shifts in the thickness of the shelf throughout the year so as to better understand the rate at which this thickness changes over time.

Continuing the study despite the Antarctic winter

The Antarctic winter is a major issue to consider, as the sun sets in the South Pole in March and doesn’t rise again until austral summer arrives in September. During this time, much of the ocean surface covers over with sea ice, making it all but impossible to continue the study. To overcome this hurdle, the group will be turning to an unlikely resource — seals.

Fifteen seals in total will be equipped with small sensors that are temporarily glued to their fur in order to assist the scientists in the continued collection of data.

The sensors attached to the seals will collect information on everything from ocean temperature to salinity to how changes in the region are affecting seal populations.

Satellites will send all collected data back to the group of scientists for analysis in their laboratory.

For those curious, the sensors the seals will be wearing are designed to fall off when the animals molt their fur.

Moving forward

Once all of this data is collected and sorted through, it will be used to improve a plethora of computer models that are used to predict future climate and sea-level rise.

“We are attempting to tackle this big science question from a number of different ice and ocean perspectives,” Karen Heywood, a professor of physical oceanography at the University of East Anglia in the U.K. and principal investigator of one of the iSTAR program's ocean investigations, said in a statement. “Our observations and measurements will be a major contribution to the ongoing, and urgent, international scientific effort to understand our changing world.”

Story via: livescience.com

Advertisement