One of the great things about 3D printing is that it offers scientists the ability to create objects with the exact properties they want. With that freedom, they are taking 3D printing to a whole new level, finding ways to add electric properties to printed objects.

Harvard University and the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign have teamed up to create printed microbatteries that can supply electricity to tiny devices.

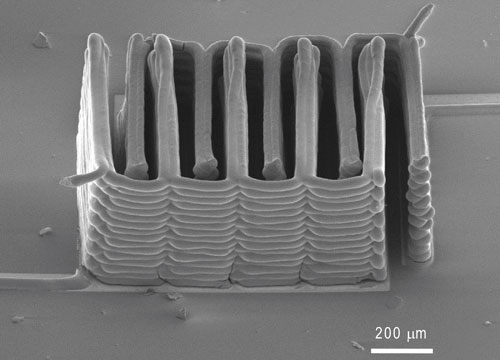

The interlocked stack of electrodes that were printed to create a working microbattery. (Image via Jennifer A. Lewis, Harvard University)

For years now, engineers have been developing “tiny” and “miniature” innovations. The only problem is, sometimes they can’t be put to use because any battery needed to power such devices would be about the same size as the device itself — if not bigger.

In order to get around this battery problem, many manufacturers set down thin films of solid materials to build electrodes, but since they need to be so thin, they often do not contain enough energy to run the device.

So many of the devices that have been created to advance the medical and communications fields have been placed on the back burner, waiting for a battery small enough to fit it, but also able to store enough energy to power it.

How to create a microbattery

To get more energy into a battery so small, the team, led by Jennifer A. Lewis, the Wyss Professor of Biologically Inspired Engineering and Applied Sciences, used a 3D printer to create stacks of tightly interlaced (and very thin) electrodes.

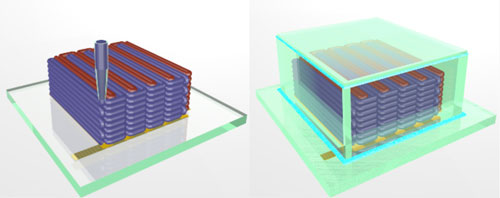

Red indicates the anode ink and purple indicates the cathode ink.

The green enclosure envelops the electrodes and creates a microbattery. (Image via Jennifer A. Lewis, Harvard University)

First, they needed to figure out a way to 3D print the electrodes so they tested special inks that could function as electrochemically active materials to create functional anodes and cathodes (each with its own ink composition). Then they hardened them into narrow layers.

The different inks were printed onto the teeth of two gold combs, creating the light and interlocked stack of anodes and cathodes. Then they were put into a tiny container filled with an electrolyte solution which completed the mini battery.

Will it work?

Finally, the researchers needed to measure how much energy could fit into a tiny battery, how much power it could deliver, and how long it could stay charged.

“The electrochemical performance is comparable to commercial batteries in terms of charge and discharge rate, cycle life and energy densities. We’re just able to achieve this on a much smaller scale,” said Shen Dillon, Assistant Professor of Materials Science and Engineering at the University of Illinois at Urbana- Champaign.

These tiny batteries could have future applications in the development of miniaturized medical implants, compact electronics, and tiny robots.

Story via Harvard University.

Advertisement

Learn more about Electronic Products Magazine