By Jean-Jacques DeLisle, contributing writer

Antarctica is a mysterious place, but even more so is the water beneath it. Scientists at the University of Washington (UW) in Seattle are hoping to unearth those mysteries with the help of a newly configured type of submersible drone called the Seaglider. And while its mission is simple, it’s not easy. These types of drones are tasked with gathering information about the melting ice sheets to help formulate predictions for how the melting ice affects the rise of sea levels.

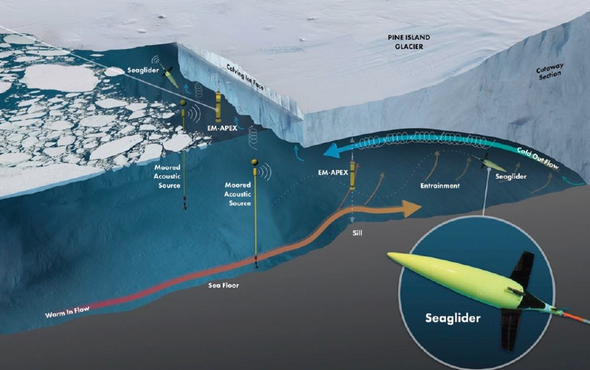

The submersible drones are set to be deployed under the Pine Island Ice Shelf, a location where ice from two of Antarctica’s largest glaciers meet the sea. During this hazardous year-long diving mission, the seven Seagliders will be accompanied by four high-tech floats, which will also be measuring temperatures as well as water currents and pressures beneath the ice.

Beneath an Antarctic ice shelf, self-steering drones called Seagliders will explore ice caves that are nearly impossible to reach. Image source: UW.

Seagliders are able to navigate through the icy water by adjusting their buoyancy and the tilt of their fins. These sophisticated motions allow them to glide slowly forward and downward into the 50-square-mile region that they are meant to explore. A unique guidance system using sonic sonar is being projected from three nearby buoys, allowing the self-propelled drones to triangulate their location even if they are deep under the barren ice shelves. These drones were not built for Antarctica’s frigid waters, but they have been refurbished to withstand this unknown icy world.

During their descent, the aquatic robots will be cut off from any signals to or from the surface by the thick ice sheet, meaning that they will have to act autonomously for the duration of their risky mission. Being completely cut off from the surface means that the seven drones will not be able to receive instructions in the event that they’re trapped under the ice, nor will they be able to call out for help. The Seagliders themselves cost roughly $100,000, so losing one to Antarctica’s unfathomable depths would be quite unnerving for UW scientists.

The four floats that will be joining the gliders are slightly different. They cannot propel themselves and are thus at the mercy of the cold ocean currents, which are expected to push them away from the ice and sink so warmer water can sweep them back inland. The floats have a price tag of about $30,000 and a drastically less dangerous job than their drone counterparts.

“There is a real risk that some of the instruments will not come back,” said Jason Gobat, an oceanographer at U.W.’s Applied Physics Laboratory. Nevertheless, they’re set to deploy for an entire year and be picked up in 2019. Hopefully they will be able to answer several questions that researchers have about the melting ice. Valid concerns to have, especially when the glaciers that they are studying contain enough ice that, if completely melted, could level every coastal city on Earth. With a better understanding of what may be causing the ice to melt, we may be able to determine how to slow down the melting process or even stop it altogether.

Advertisement

Learn more about Electronic Products Magazine