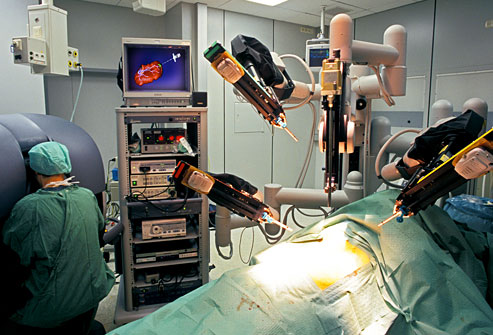

A safety study conducted by researchers at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, and Chicago's Rush University Medical Center, has found that robotic surgeries performed over the past 14 years has led to 144 deaths and more than 1,000 injuries in the US.

Among some of the recorded events: broken instruments falling into patients’ bodies, electric sparks that led to tissue burns, and system errors that resulted in surgeries taking longer than planned.

Speaking to the specifics, there were 144 deaths, 1,391 injuries, and 8,061 device malfunctions out of a total of more than 1.7 million robotic procedures between January 2000 and December 2013.

Reports were submitted to the group by hospitals, patients, device manufacturers, and others to the US Food and Drug Administration.

The authors note these numbers could be higher, as there were several reports not recorded in the published report.

“Despite widespread adoption of robotic systems for minimally invasive surgery, a non-negligible number of technical difficulties and complications are still being experienced during procedures,” the study states. “Adoption of advanced techniques in design and operation of robotic surgical systems may reduce these preventable incidents in the future.”

While the numbers recorded in this study might seem a bit high, they should be treated with a bit of caution. One reason is due to – as the authors note in the study – the fact that “little or no information was provided in the adverse incident reports” about the cause of most of these deaths. This means the deaths may not be due to a malfunction on part of the robot performing surgery, but rather risks or complications inherent during surgery.

Some other things the authors did not record: the level of complications in surgery where robots aren’t used, and there was no examination done as to the benefits of robotic surgery.

So, with all of that being said, let’s take a closer look at the data the team did record. For one, the number of injuries and deaths per procedure has remained fairly consistent since 2007. This might seem like a good thing, as it would appear the roboticists behind these machines have figured out a way to moderate the level of risk associated with this modern-day solution, but it’s actually the complete opposite: the authors note the use of robotic systems is increasing “exponentially”, meaning the total number of accidents is actually increasing every year, but due to their increased usage, the percentage of recorded accidents is staying the same.

Another thing worth noting: when technical problems occur, people are significantly more likely to die if the surgery involves the heart, lungs, head and / or neck; this, as opposed to gynecological or urological procedures. The authors admitted their data does not pinpoint why this is the case. Instead, they suggest it could be due to these types of procedures being more complicated, and the fact that the robots may not be programmed with enough skill to perform the procedures as say, a surgeon with thousands of these surgeries to draw upon as reference.

Lastly, while the study reports hundreds of injuries and deaths linked to robotic surgery, in most of the FDA’s logs, it is not exactly clear whether the use of machines was directly responsible. Specifically, five of the deaths and 436 injuries have a long enough paper trail to be tied to technical errors on part of the robot. Take, for instance, the 1,166 cases where broken / burned parts fell into patients’ bodies: of these incidents, there were 119 injuries and one death. Spontaneous powering on / off and uncontrolled movement of the machines led to 52 injuries and two deaths. Electrical sparks, unintended charring, and damaged accessory covers are linked to 193 injuries (commonly burned body tissue). And loss of video feed and / or system error codes contributed to 41 injuries and one death.

Regardless of how you, the reader, take these numbers, one thing that can be agreed upon is the fact that they can be improved upon. And in the study, the group suggests one way to do this is to begin giving surgical teams more troubleshooting training; that is, not training that is exclusive on how to use the machines but rather, instruction that also includes what to do when things go awry. This will better educate them as to how to restart a surgery more quickly after an interruption occurs.

Via BBC

Advertisement

Learn more about Electronic Products Magazine