BY MARTIN ROWE

Senior Technical Editor, Test & Measurement

EDN and EE Times

www.edn.com , www.eetimes.com

Concern over test costs is nothing new, but this time, there’s a difference. That became clear at a panel session held at the 2017 IEEE International Microwave Symposium (IMS) in June and at the 2017 IEEE EMC+SIPI Symposium “Ask the Experts” panel session held in August.

What’s different this time? It’s about low-cost, low-power consumer devices being developed by thousands of small companies and some large ones. In most cases, these devices will connect to the internet, often over a wireless connection. Designers of these devices may lack RF design experience, even if they’re electrical engineers. These designs may incorporate Wi-Fi or Bluetooth connectivity while others use cellular data connections.

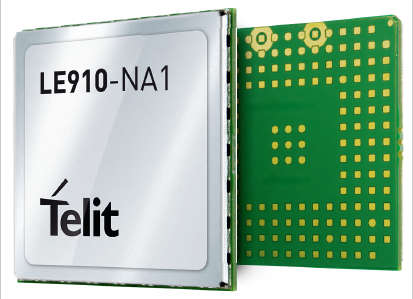

Devices that use Wi-Fi and Bluetooth connectivity may simply design in a module that incorporates RF components such as transceivers and power amplifiers (Fig. 1 ), and possibly even antennas. Startups likely can’t afford wireless test equipment. For production, they may simply test a device by verifying that it connects to a wireless access point or Bluetooth device. Fig. 1: An RF module from Telit adds connectivity to T-Mobile’s LTE network. Image Source: Telit.

Fig. 1: An RF module from Telit adds connectivity to T-Mobile’s LTE network. Image Source: Telit.

Simple tests mean that designers rely on RF module manufacturers for some testing. At the IMS panel, Jason White of National Instruments noted that consumer devices will put pressure on module and semiconductor companies to do more testing. “Digital content in ICs is being replaced by RF content,” said White. “That’s changing how IC manufacturers test their products. IC testers will need to become more flexible and adapt to those needs.”

Simple “go/no-go” connectivity tests may be acceptable as long as the product works, but what happens when it fails? That’s when more measurements will be needed and, thus, more sophisticated (and more expensive) test equipment. Because of that price pressure, we’re seeing lower-cost test equipment such as spectrum analyzers and network analyzers appear on the market. Just because an RF module works doesn’t mean that it will work when integrated into a product. At the IMS panel, Chris Scholz of Rohde & Schwarz explained that antennas and signal paths can affect performance, something those who lack RF inexperience might not realize.

Devices that connect to cellular networks need more rigorous testing; carriers want to be sure that devices connecting to their networks will properly communicate. A few years ago, Verizon set up Innovation Centers in Waltham, Massachusetts, and San Francisco, where designers can, for a fee, bring their products in for testing with simulated networks.

With 5G coming, test costs for cellular connectivity will surely go up, at least initially. That’s because early products will need intense characterization and interoperability testing. While early 5G networks will likely operate at frequencies below the popular 6-GHz ceiling, we’ll later see millimeter-wave (mmWave) frequencies come into use for the first time in high-volume products.

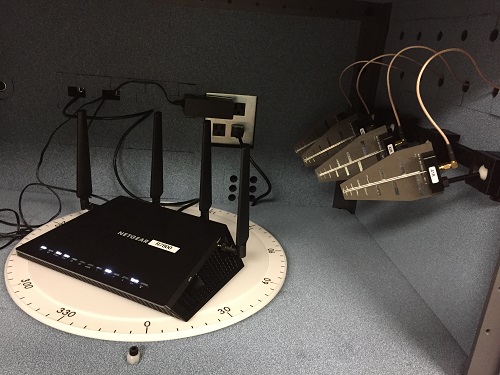

At mmWave frequencies, wireless modules may indeed have integrated antennas, which will require over-the-air (OTA) testing for devices. Such tests need to be conducted with the DUT in a chamber (Fig. 2 ) as opposed to using a cable. Fig. 2: Over-the-air tests are performed in small chambers such as this one from octoScope.

Fig. 2: Over-the-air tests are performed in small chambers such as this one from octoScope.

Another issue regarding low-cost devices arose at the IEEE EMC+SIPI Symposium. During a signal-integrity panel session, someone asked if anyone will perform signal-integrity tests on low-cost devices. This caught the panelists by surprise, with a few admitting that they hadn’t thought of it. The discussion went beyond test as the audience member noted that designers are creating devices that are just good enough in performance to meet price and battery-life requirements.

Advertisement

Learn more about Electronic Products Magazine