Human fertilization is analogous with shelling a target during World War I—fire enough rounds of ammunition and the law of average declares you’ll eventually hit your target. That odds may not be favorable, but that’s why we rely on shear volume—200 to 500 million “shells” to be precise. Researchers from the Dresden Institute for Integrative Nanosciences are testing a new approach that targets one of the primary causes of infertility: healthy sperm with poor mobility.

The team is developing a solution called “spermbot,” a magnetically-driven add-on that turns sperm into remote-controlled robots that can be piloted all the way up to the egg. Such an odd approach may seem unnecessary given the existence of artificial insemination and in vitro fertilization, but these techniques are expensive and do not guarantee fertilization if the underlying issue stems from the sperm’s inability to swim. Spermbot is more reliable as it fills in for biological mishaps and delivers the sperm directly to the egg.

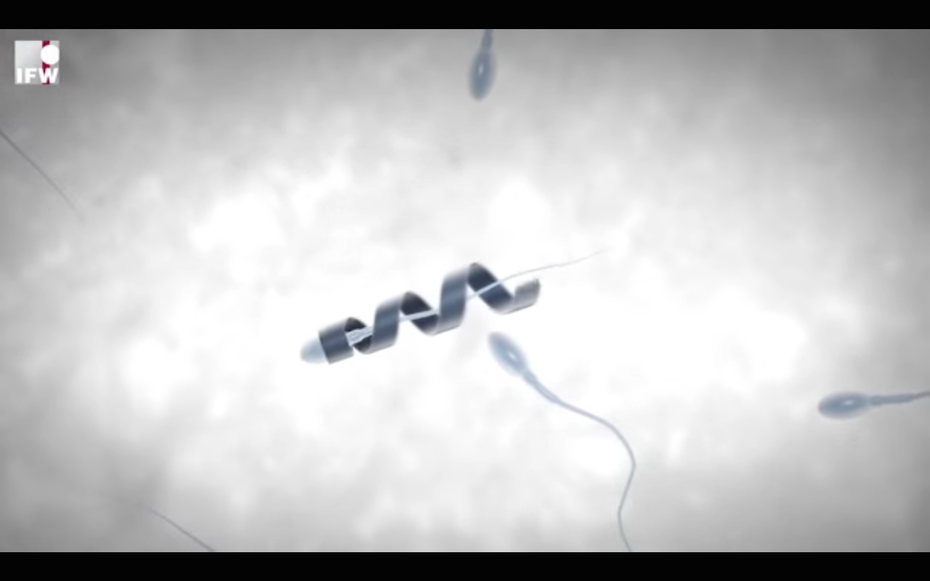

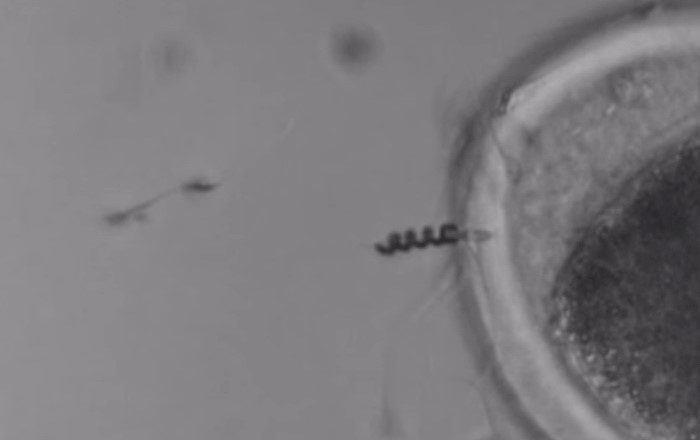

A previous iteration of the spermbot was introduced in 2014, which placed live sperm cells within microscopic tubes made out of titanium and iron that relies on magnetic fields to move the bot from point A to point B. The 2016 edition trades the metallic tube for a metal-coated polymer microhelix which attaches to the sperm’s axial filament (tail) and acts as a micromotor.

“We have chosen magnetic helices as micromotors because of their relatively simple mechanism of motion that is widely understood and easy to control in 3D by a common setup of axial pairs of Helmholtz coils,” the researchers explain in their research paper.

Once a rotating magnetic field is introduced, the microhelix spins, propelling it and the attached sperm forward. To steer the sperm in 3D space, researchers simply adjust the orientation of the magnetic field and pilot the robot directly into the egg. It’s unclear what happens to the microhelix at this point.

Overall, it’s a very straight-forward and effective practice that has been successfully demonstrated in a Petri dish, though will be eventually conducted using an MRI machine. That’s not to say that all kinks have been worked out. The team require some more research and fine-tuning before the robot moves into clinical trials.

Advertisement

Learn more about Electronic Products Magazine