Power supplies are the underpinning of any electronic system. In this article, I use industry research and my own long-time experience to present the five reasons that power supplies fail (PSU). It will also offer the necessary precautions that you, as design engineers, should take to avoid systems failures.

Power supply data

The power supply data analyzed for this article is based, in part, on studies conducted by Excelsys in many applications all over the world and also on the North American power supply refurbishment/repair company, Power Clinic. Since 1987, Power Clinic has collected data on power supply failures covering over 12,000 different models sent in from over 1,600 different companies. This includes data from more than 1,700 units sent to them in 2015 alone, giving you an idea of how many non-working power supplies are seen on a routine basis.

In order to cover all power industry segments, this article also relies on analysis of a study done by Dr. Ray Ridley of Ridley Engineering based on input from his LinkedIn “Power Supplies” group. The group has over 6,000 members who weigh in on the topic.

The data analyzed from these sources spans across all markets and applications, including industrial, medical electronics, military, telecom, datacom, and computing and scientific fields. It includes the most common power electronics applications, from low-cost to extremely high-cost, including flight simulators, digital signage, medical equipment test and measurement equipment, and semiconductor equipment.

Power supplies or products such as ATX power supplies or a product meant for ultra-low-cost applications were not analyzed because it’s difficult to get data on returns intended to be disposable.

Top causes of power supply failures

A fundamental law of physics is that for every 10°C that you are able to keep the power supply’s environment lower than 40°C, you double the mean time between failures (MTBF). Conversely, for every 10°C your power supply’s ambient temperature increases, your MTBF cuts in half (that is, your power supply is half as reliable). Many, but not all, of the failure mechanisms on this list are related to temperature.

More and more, we’re seeing the use of end-equipment plastic chassis compared to the metal chassis that have been used since time began, which impacts thermals as well as EMC. Anything you can do to enhance thermal management around your power supply in the system is of critical importance.

1. Fans

Fans are the number one failure mechanism of power supplies, as found by both military MTBF simulations as well as Belcore standards and as both simulated and demonstrated in reality. As the only electromechanical moving part incorporated into power supplies, fans are prone to fail even in the most properly designed power supplies. Often, we see a no-fans requirement for the power supply only to have the end user add fans to get rid of the heat of the entire system. But this approach just transfers the problem from one place to another.

Another problem in the industry is the proliferation of counterfeit fans into the supply chain. In one case that I know of, a customer discovered a substitute fan they bought that was indistinguishable from the original — except that it moved 30% less air and consumed different power than the original. It is important to make sure that your power supply partner has processes to keep counterfeit parts out of the supply chain; otherwise, that low-cost power supply is going to get expensive very quickly.

A fanless system can be sealed, which also eliminates other issues, including ingress of moisture. In the case of outdoor applications, such as digital signage, a sealed system can keep out leaves, bugs, twigs, and bird nests, as well as rain and moisture and, in the case of maritime applications, salt and fog.

Removing the fan increases reliability by 25% and is the best solution for avoiding failure. A good design that keeps the efficiency of the power supply high enough makes fans unnecessary.

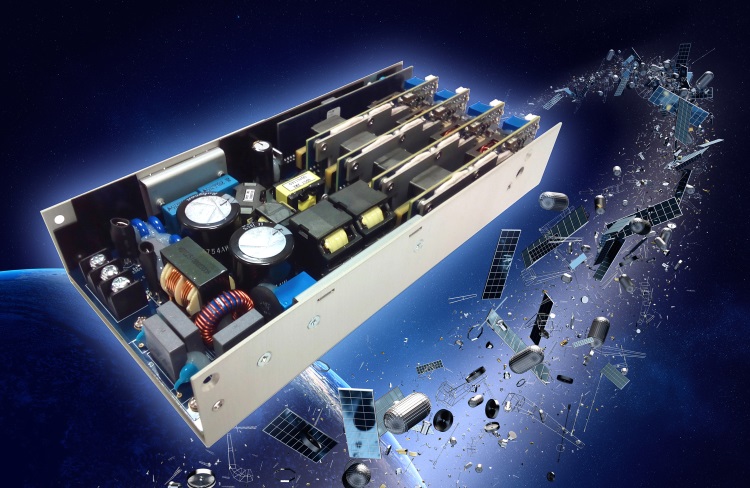

The key to good power electronics design is: “don’t need a fan if you can help it.” To address this need, Excelsys recently introduced a convection-cooled modular power supply that delivers 600 W of output power without using fan-assisted cooling (see Fig. 1 ).

Fig. 1: The CoolX 600 Series fanless power supply offers very high input and surge-withstand built in.

2. Capacitors

Despite popular thought, a lot of progress is being made in capacitor technologies every year; however, they are prone to failure if overstressed or if substitutes are made in production or by counterfeiting.

Capacitors, especially electrolytics, can be found failed in many different failure states, including swollen, leaking, exploded, shorted, reduced-capacitance, or increased-in-circuit ESR. Sometimes excess heat causes capacitor damage. Electrolytic capacitors can leak chemicals, which can then cause further damage from corrosion, eating away PCB traces, and other problems (see Fig. 2 ).

Fig. 2: This example shows the damage caused by leaking electrolytic material from a capacitor.

To prevent failures, use high-quality capacitors from name brands. Also, derate. Keep capacitors as cool as possible and watch the ripple currents to make sure they are not excessively stressed. It’s important to know that storage life of electrolytic capacitors is limited to two years without power on the power supply, which is something that usually gets overlooked. As power designers, we avoid electrolytic capacitors if we can, but if we can’t avoid them, we get the best that we can find. (We specify two years of unpowered storage maximum to avoid the electrolyte from becoming affected by the long-term unpowered storage.)

3. Power components

Power switching components, or MOSFETS, which take the brunt force of operation of the power supply, can sometimes cause failure if the heat sinking is inadequate, or if the drain overvoltage, drain overcurrent, gate overvoltage, or the internal antiparallel diode is overstressed.

Proper design and the derating of components will go a long way to help the MOSFET have a nice, long life in the application. Proper design, attention to the control circuitry, loops testing, and derating can ensure proper operation and long life of these components.

Power diodes can also fail due to improper heat sinking or thermal management, airflow, and such. Schottky diodes can be damaged by overvoltage in driving inductive circuits. They are not as forgiving as MOSFETs during overvoltages. Also, switching losses in rectifiers can be a large source of heat. TRR tails can occur when switching time extends a bit with temperature, causing the heat to rise, and a positive feedback loop can occur and the part can be damaged. This potential problem must be carefully considered during design to keep the dissipation low. Proper design, component selection, and characterization, along with derating, will do wonders.

4. Control ICs

Control ICs often have an unusual region of operation and, if misunderstood or misapplied, can lead to failure. This includes incorrect clock operation or improper PCB layout, which will make the control IC susceptible to noise or oscillation. All controller ICs have their own unique behavior and need to be well-understood in the application, including the work-arounds and “undocumented features” for the intended application.

To avoid failures with commercial control ICs, start-up conditions must be understood. Current limiting, soft-start modes, proper gate drive, spacing, and measuring the control loops — all must be done to ensure stable operation over all conditions. The control ICs must work perfectly every time; otherwise, damage will likely be seen in the MOSFETs because they take the brunt of the energy when the control IC fails or becomes unstable. With digital controllers increasingly being used in power electronics designs, we see software and control ICs being one issue, and sometimes it is the control IC that fails; however, it’s usually the switching MOSFETs that end up being taken out.

5. Environmental causes

Environmental issues from moisture ingress is sometimes seen in medical electronics when equipment is cleaned with disinfecting solutions that enter the power supply’s ventilation openings and fan ports (another reason to eliminate fans). Moisture will corrode the electronics and eventually lead to failures. Other failure modes from the user environment include surges and transients that are well above the ratings and many IEC standards, which usually damage the semiconductor components in the front end of the power supply. Some of these environmental concerns can be controlled by design in the application and some cannot.

Other environmental problems are lightning strikes and other induced power-line surges and transients (see Fig. 3 ). The toll from these causes can be minimized by careful design and test of the power supply and by adding external protection components. For example, there are excellent surge-protection devices from Littelfuse, such as the LSP10240 series, that can handle tremendous transients and surges to protect the AC input of a system. Newer power supplies have surge protection designed into them and some are also designed to handle 300 Vac for five seconds, since power-line stability globally is not a guarantee.

Fig. 3: This photo shows burned capacitors caused by an open-air arc from a lightning strike.

Other environmental considerations are loads — reactive loads such as regenerative motor drives, battery charging, super-caps, and more. Loads should be considered and, potentially, protection circuits like diodes can be added. In your application, this could prevent 250 V from a motor-turned generator from being applied to the 24-V outputs of your power supply.

In many of the applications I work with that have reactive loads, the problem is solved by reactive load modules like the XGR and XGT modules from Excelsys. These modules employ bypass diodes and blocking circuitry built in, thus eliminating the need for any external circuitry to protect the power supply from back EMF. This approach often does wonders.

How to prevent power supply failure

There are other conditions that can cause power supplies to fail but, based on the research, the ones I’ve described happen most frequently. When designing a system, the main rule is to make the power supply itself the first consideration — not the last.

Engineers should try to eliminate the fan by using a fanless power supply, if possible. They should also use legitimate components and create a well-designed, robust system. It is also important to choose a power supply partner that offers a extended warranty to help ensure that they know what they are doing. But it is also vitally important for the engineer to understand the warranty. For example, when your low-cost power supply fails, it might mean that when you place your next 1,000-piece MOQ order from a far-off land, you will be shipped a new power supply. However, that solution doesn’t begin to pay for the cost of the expense of the failure.

A high-quality power supply company will take the lessons learned from experience and incorporate them into new designs to increase reliability and reduce field issues. And offering a long-term warranty means that you won’t have any issues in the field in the first place.

By KEVIN PARMENTER

VP NA Applications Engineering

Excelsys Technologies

www.excelsys.com

Related articles:

Advertisement

Learn more about Excelsys