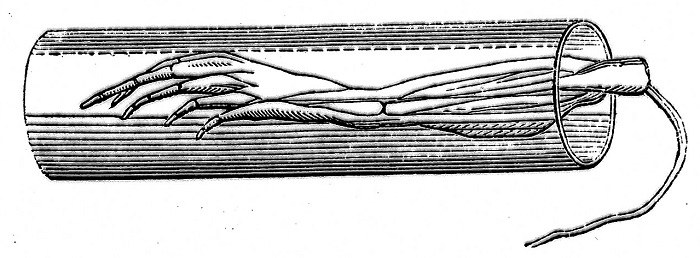

The sketch above is the frog galvanoscope, a super-sensitive electrical instrument used in the late 18th and early 19th centuries to detect voltage.

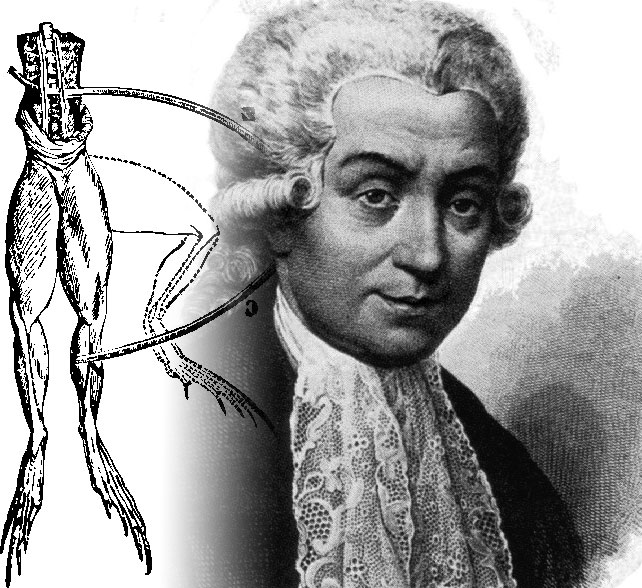

The instrument was invented by Luigi Galvani. In 1780, he was researching the nervous system of frogs for the University of Bologna, a school where he often lectured. The research included the frog’s muscular response to stimulants like opiates and static electricity, and required Galvani’s removing the spinal cord and rear legs of the frog (and skinning the latter) for testing purposes.

During one particular set up, an electric machine discharged when Galvani’s assistant touched the crucial nerve of a dissected frog with a scalpel. This caused the frog’s leg to twitch and at that moment Glavani realized that he could make the prepared leg twitch simply by connecting a metal circuit from a nerve to a muscle. This led to the invention of the frog galvanoscope, and a paper by Galvani describing the results of its use in 1791.

Thereafter, Galvani and his nephew Giovanni Aldini used the frog galvanoscope in multiple electrical experiments. Eventually, Carlo Matteucci heard about the instrument, and went on to improve up on it before bringing it to wider attention.

In terms of how the instrument is constructed, an entire frog’s hind leg is removed from the frog’s body with the sciatic nerve still attached. The leg is skinned and two electrical connections are made, most often with one to the nerve and the other to the foot; everything is then wrapped with metal wire or foil.

Matteucci’s improvement was to simply place the leg in a glass tube with only the nerve protruding — connection is then made to two different points on the nerve.

Per Matteucci’s approach, his thoughts were that the frog galvanoscope is most accurate if direct electrical contact with the muscle is avoided, and that the nerve should be well stripped and contacts made with wet paper (in order to avoid the sharp metal probes damaging the nerve).

Regardless of whether it’s a Galvani or Matteucci design, when the instrument is connected to a circuit with electric potential, the muscles contract and the leg will twitch; it twitches a second time when the circuit is broken. It proved quite capable of detecting super-small voltages — so much so that it was still the preferred instrument to use well into the 19th century when alternative tools like the electromagnetic galvanometer and gold-leaf electroscope were being introduced.

The major drawback about the frog galvanoscope (outside of all the modern-day concerns that would be tied to using an instrument like this) was the fact that the frog leg needed to be constantly replaced. On average, the typical usage period for a frog leg in this instrument was approximately 44 hours; afterwards, a new one needed to be prepared.

Advertisement

Learn more about Electronic Products Magazine