Useful in everything from particle physics to data encoding, lasers have proven useful in a multitude of fields since Theodore H. Maiman built the first of such devices in 1960. Interestingly, few people realize that the word “laser” is actually an acronym for “light amplification by stimulated emission of radiation,” and that white lasers have never actually existed — at least, until now. Researchers from Arizona State University have demonstrated that a new kind of semiconductor is able to emit laser across the entire visible light spectrum, unlocking a potential in lighting and light-based wireless communication.

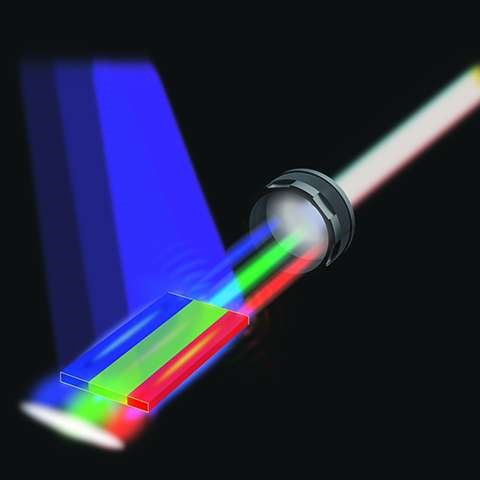

The laser emitting device was constructed from three parallel sheets of semiconductor a few microns thick (one-thousandth of the thickness of a human hair), each capable of shining laser in one of the three colors, but together, tunable into any color in the visible spectrum including white. This ability produces greater luminous and energy efficiency than LEDs potentially allowing the creations of displays with superior accuracy and vibrancy equitable to 70 percent more colors than the current industry standard.

Combining light from multiple lasers to produce white laser has previously been accomplished, but never in the same scale as the researchers from ASU; their device shrinks the hardware into a single unit, creating the possibility of integrating the device into real working technology.

Aside from display, one interesting application consists of visible light communication called Li-Fi, a system that encodes communication data in the same lighting used for illumination. Li-Fi is still under development, but the approach is a step up from Wi-Fi, which relies on radio waves to encode and transmit data. An LED-based Li-Fi system is approximately 10 times faster than Wi-Fi, whereas one centered on white laser can reaches performance levels of 10 to 100 times faster.

Light-emitting semiconductors are usually made from a solid chemical element or compound arranged in crystals that emit light in a specific color when a voltage is applied. This color is determined by the material used to create the semiconductor and its unique atomic structure and energy bandgap. The challenge, thereby, is to achieve a single semiconductor capable of fulfilling the multiple requirements needed to produce all possible wavelengths in the visible light spectrum but remains small enough for hardware application. The solution lay in nanotechnology. For an in-depth look at research 10 years in the making, have a look at the journal Nature Nanotechnology where the results are published.

Source: Phys.org

Advertisement

Learn more about Electronic Products Magazine