It costs approximately a quarter of one’s average monthly salary to gain a single hour of Internet access in Old Havana’s last remaining government-run Internet café. In Cuba, home Internet connections are illegal for all save a handful of citizens, forcing the majority of the island’s inhabitants to live cutoff from mainstream information and contact with family and friends abroad. Taking matters into their own hands, some enterprising Cubans created their own private Internet, stretching miles of cables across the roofs of Havana.

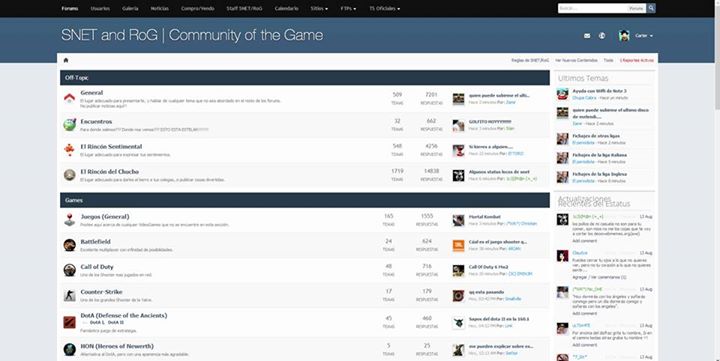

Since 2001, a small but growing community of tech-aficionados has pooled their resources together to create a hidden mesh of broadband cables and Wi-Fi antennas linking 9,000 computers across different neighborhoods of Cuba’s capital. The resultant network, dubbed SNet, or streetnet, allows its participants to exchange news updates, share movies and music, chat, participate in homegrown social media, and even host private servers that enable them to play video games like World of Warcraft and a pirated edition of one of the Call of Duty’s.

While SNet is limited, local, and disconnected from the real Internet, it still receives a regular influx of new television content and movies smuggled in by users with true access. There’s even a copy of WikiPedia that’s routinely updated as well.

“We aren't anonymous because the country has to know that this type of network exists. They have to protect the country and they know that 9,000 users can be put to any purpose,” Rafael Antonio Broche Moreno, a 22-year-old electrical engineer who helped build Snet, told the Associated Press recently. “We don't mess with anybody. All we want to do is play games, share healthy ideas. We don't try to influence the government or what's happening in Cuba … We do the right thing and they let us keep at it.”

What’s more, the very equipment linking the SNet network is illegal without a license from the Ministry of Communications, but the government turns a blind eye so long as users to don’t connect to the real Internet, discuss politics, or share pornography. As a result, the network polices itself with volunteer administrators that informally monitor traffic; keeping users in check is central to remain online. The penalties for violating regulations range from a one day ban to a permanent ban.

Although Cuba remains one of the least wired nations in the western hemisphere, its youth are hopeful that the new relationship being forged with Obama administration will expand U.S. technology sales on to the island — thus, widening SNet access — and set the wheels in motion from political reform. The hardware currently available severely bottlenecks how far SNet can expand.

“It's proof that it can be done,” said Alien Garcia, a 30-year-old systems engineer who publishes a magazine on information technology that's distributed by email and storage devices. “If I as a private citizen can put up a network with far less income than a government, a country should be able to do it, too, no?”

Source: AP

Advertisement

Learn more about Electronic Products Magazine