The electric vehicle, for many reasons, has always piqued our interest, as a driving public. Driving electric is considered green for the environmentally aware; it’s a conversation starter for the geek-minded because it is so technologically advanced; and it offers the thrill of serious acceleration for the driving enthusiast. The new automotive platform has something for almost everyone. It’s missing the most critical link for making it a success for buying public — charging stations. No one wants to get stuck without the juice to travel further on up the road. Well, that may be about to change, according to a new report, DC Charging Map for the United States, from Navigant Research. I know what you’re thinking: this isn’t new because Tesla offers that now. That’s true, but those charging stations are only for owners of Tesla cars.

The report is inclusive because it targets the stakeholders, such as the automakers, charging equipment companies, utilities, and government agencies. These stakeholders need to consider how to optimize their significant investments by placing stations where demand is most likely to occur, due to the presence of large battery electric vehicle (BEV) populations and frequently traveled highways and interstates. The research makes an aggressive prediction that it would take only 95 stations to provide basic long-distance travel along the East and West Coasts and across the country. Additionally, coverage in the top 100 metropolitan statistical areas (MSAs) by population in the United States could be achieved with a total of 408 charging stations.

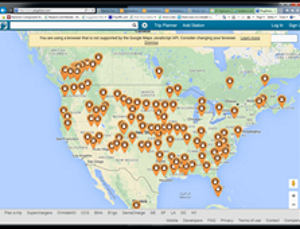

Example map from a PlugShare interactive map for DC fast charging stations.

This is not just a map that provides information to all of the stakeholders. It also offers the information about the reason why DC fast charging will shift to higher power levels than the 24-kW and 50-kW fast chargers available today. The report determines how many fast charging stations are needed for long-distance travel and where to place them in a staged rollout. It also offers a map of proposed low-power DC charging stations that are designed for drivers within the major metropolitan statistical area.

These DC fast chargers, as the name implies, charge much more rapidly than, say, your home’s electric vehicle service equipment (EVSE). One of the reasons that the fast chargers replenish energy more quickly is because they bypass the car’s on-board charger, providing DC electricity directly to your battery using a special charging port. Yes, Tesla already offers this, and at a higher charging rate — but it’s only for Tesla owners. This report separates charging into high-power fast charging and low-power, slower charging. I will guess that the report talks about the average time it takes for cars to recharge on the high-power vs. the low-power charging stations because providers and drivers will need to know that for travel. For example, the BMW i3 has an electric range of only 81 miles, and takes 20−30 minutes to charge to 80% (about 65 miles) using a DC fast charger. However, a low-power charger would provide only about 25 miles of charge per hour — something you would want to know. I wonder if these charging stations will lead to the creation of EV rest, entertainment, or even Wi-Fi hotspot areas, because time is valuable. Additionally, this is a very different scenario than the gasoline-powered car that needs only a matter of minutes to re-fuel, and drivers have to be able to calculate drive times.

The report suggests a four-phase rollout of the charging stations so that it happens in a logical way and doesn’t leave motorists stranded. What I didn’t find mentioned in the report was any suggested pricing differential between the high-power and low-power charging. I suppose that the market will figure that out. You can download an executive summary of the report from the Navigant Research website.

Advertisement